|

It is some time since I last played a 17th Century game but earlier this year I was tempted back after reading Michał Paradowski’s new book published by Helion, “Despite destruction, misery and privations” about the Polish army fighting the Swedes in Prussia in the 1620s. This fascinating book is full of detailed information about the recruitment, equipment and organisation of the Polish forces. I rather wish it had also described the course of the war, if only in general terms, for the benefit of non-Poles like me who don’t already know the history. But I still strongly recommend it to anybody with an interest in the period. Over the years our gaming group has tried a few rules sets for 17th Century Battles in Eastern Europe. My favourite for some time have been Tercios by el Kraken, but the need to issue a separate order card to every unit can make bigger battles a bit slow to play. When Simon Miller and Andrew Brentnall released ‘For King and Parliament’ three or so years ago, I picked them up because I really like Simon’s Ancients rules, ‘To the Strongest’. FK&P doesn’t have rules for several east European troop types but they are easily adaptable. With a bit of borrowing from To the Strongest, I drew up some house rules to adapt FK&P to battles further east. We played a test game based on Berestechko, 1651, which went well. I then started on troop stats for 1660, which added Muscovite troop types to the mix. At that point I was distracted by a rebasing project for my 15mm Napoleonics and 1660 went onto the back burner. Thanks to Paradowski, I have now hauled it out again and done some more work on the house rules and troop stats, and have written a couple of scenarios to test them. The latest house rules are here Two scenarios for the price of oneThe scenarios are set during the 1660 Chudnov/Cudnów campaign, between the Commonwealth and Tatars on one side and a Muscovite-Cossack alliance on the other. I love taking ideas from this campaign! It offers several candidates for an interesting game, including a clash of advance guards, a running fight, a rearguard action at a ford, a field battle and an assault on the enemy camp. Both of the new scenarios are based on the third day of the battle of Lubar on 16 September 1660. The historical version represents an attack by the Poles and Tatars on the enemy camp. The second is a What If scenario, involving a battle in the open ground between the two camps. This scenario presumes the Poles adopted a battle plan supposedly put forward by Field Hetman Lubomirski. Both scenarios can be found here. We played the What If version as a multiplayer scenario in 2014 using Warlord Games’ Pike and Shotte and It gave a balanced game. I later converted the orders of battle for the Tercios rules and we played the historical battle in 2016. Last week I played the historical FKaP scenario with Chris and Paul and will play it again this Friday with two more opponents, Kevin and Rupert. I will post battle reports and photos after the second game. Meanwhile, as English language accounts are hard to come by, I have written an account of the battle below. It is based on a few sources, mainly Łukasz Ossolinski and Mirosław Nagielski. The battle of Lubar 16 September 1660

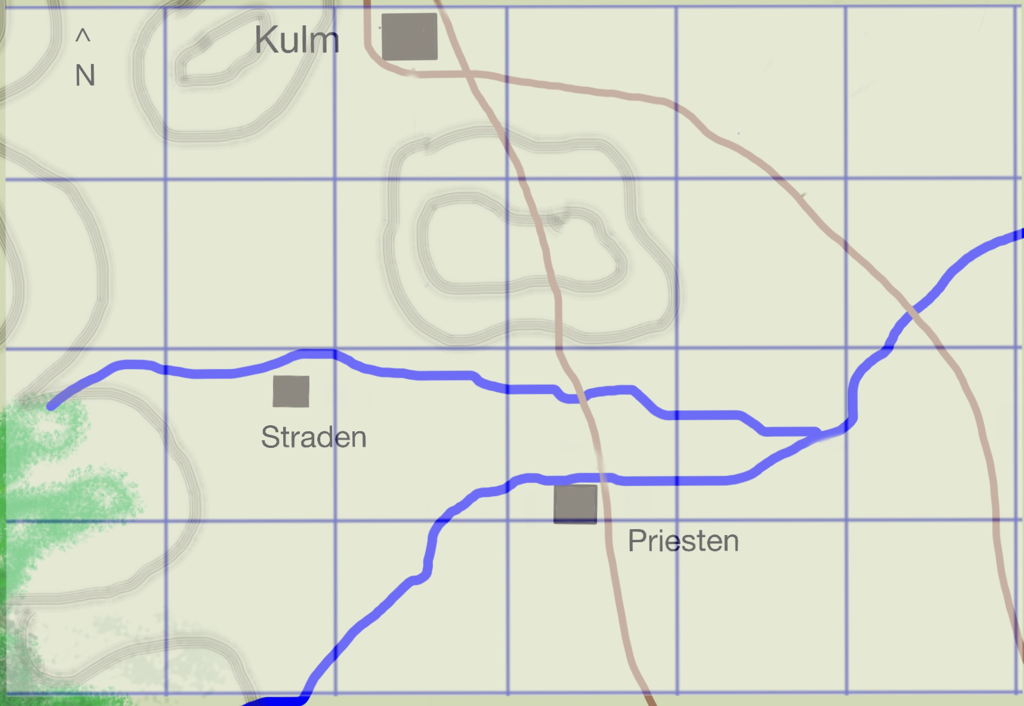

The battle of Lubar was the first act of the Chudnov campaign of 1660, when a Muscovite-Cossack alliance took the field against the armies of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and their Tatar allies in Ukraine. Lubar was in fact a confrontation over several days. It began on 14 September with a chance encounter between the vanguards of the Commonwealth-Tatar army and the main Muscovite-Cossack army led by Sheremetyev and Tsetsura. Having made contact, the two sides made camp within a few kilometres of each other. At this time it was standard practice to fortify in the presence of the enemy, first by placing wagons around the perimeter and if a long stay seemed likely, by digging earthworks. After the initial clashes of the 14th, both sides spent the 15th strengthening their camps and preparing for battle. The Commonwealth and Tatar camps were placed near the town of Lubar, with easy access to fresh water and forage. Sheremetyev and Tsetsura’s camp was well situated for defence with forest to its rear and an emplacement on high ground covering its southern side, facing the enemy. However, it was poorly suited to a long stay, as forage was scarce and its water supply was a marshy stream that was barely able to meet the needs of 30,000 men and their livestock. On 16 September, the opposing forces drew up in battle array, facing each other between their camps. The Commonwealth army had an interest in fighting in the open, where it could take full advantage of its superiority in cavalry. The enemy was believed to be unaware that Field Hetman Lubomirski and his division had arrived in theatre to join Grand Hetman Potocki. According to some accounts, Lubomirski proposed setting a trap, by hiding his troops behind high ground and drawing the enemy further into the open before launching an ambush. For whatever reason, no trap was laid and the whole Commonwealth army advanced on the enemy. In response, Sheremetyev withdrew the bulk of his army back behind his camp earthworks, leaving two forward garrisons: the fortified hill in front of his left, occupied by infantry and artillery with cavalry hidden behind the hill; and trenches in front of his right, occupied by Tsetsura’s Cossacks with light artillery. The action began with an assault by Potocki’s Command on the Muscovite-held hill. The first attack, by Polish dragoons, overran the position and forced the enemy infantry out. The Muscovites counterattacked and retook the hilltop, to be ejected in turn by some of Potocki’s ‘foreign’ foot. Meanwhile a cavalry fight developed around the base of the hill, with both sides feeding in reinforcements. The hilltop may have exchanged hands again in the course of the fight but by late afternoon it was in Polish hands and the Muscovite forces had withdrawn to their main camp. With the hill in his possession, Potocki ordered his troops to prepare to assault the main enemy camp. However, as his infantry formed up in front of the Muscovite earthworks it was disrupted by heavy artillery bombardment and this evidence of Muscovite determination, combined with the advanced hour, prompted Potocki to call off the assault. On the Commonwealth left flank, Lubomirski’s infantry attacked the Cossack forward trenches and eventually cleared them. Again, given the late hour, Lubomirski did not wish his troops to go on to attack the main camp, from which the Cossacks kept up a determined fire. At this point, according to Polish eyewitnesses, an incident occurred that led to the fight restarting. Throughout the day, the Tatar contingent had been coming and going from the field, harassing the enemy with bow fire and looking for weaknesses around the enemy position. Shortly after the Cossack trenches had been cleared, a senior Tatar warrior fell wounded from his horse in front of the enemy camp and a group of Cossacks jumped out from behind their earthworks to take him prisoner. Seeing this, those Tatars in the vicinity rounded on the Cossack group, saved their wounded comrade and amidst the confusion, pursued the enemy back inside the camp. More Tatars followed and were joined by Polish horse and a regiment of foreign foot, all of whom broke into the Cossack earthworks. The infantry commander believed the Cossacks were breaking and urged that the breach be exploited, but Lubomirski insisted that all troops return to Polish lines. The day therefore ended with the Commonwealth army abandoning its gains on both the left and right wings and retiring to its own camp. The fighting on 16 September illustrated the strengths and weaknesses of the opposing armies. Sheremetyev and Tsetsura were outclassed in the cavalry arm so unlikely to win a battle in the open. Potocki and Lubomirski meanwhile had too few infantry to carry the enemy camp by storm. Sheremetyev decided to stay behind his earthworks and wait to be reinforced by Chmielnicki’s 20000-strong Cossack army, which was only a few days’ march away. Potocki and Lubomirski laid siege to Sheremetyev’s camp. Over the days that followed, the Muscovite/Cossack camp, hemmed in by the Commonwealth/Tatar blockade, began to suffer from the poor water supply and limited access to fodder. Moreover, Chmielnicki showed no signs of advancing to reinforce Sheremetyev, despite exhortations to hurry up. On 26 September Sheremetyev retreated to his forward supply depot at Chudnov, pursued a little belatedly by the Commonwealth army. The next day, the two armies settled down again in much the same situation as before, with Sheremetyev blockaded in his camp by the Poles and Tatars. There would follow several minor engagements, a battle at Słobodiście and the desertion of his Cossack allies before Sheremetyev was forced to surrender and marched his army into captivity. As events turned out, the confrontation at Lubar on 16 September had been the high point of Muscovite fortunes.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed