Why write about this?

I have owned a collection of East European Renaissance figures since 1986, when I bought a Polish and a Muscovite army, ready painted, from Lancashire Games. I had just moved to Warsaw and wanted to game a new period relevant to where I would be living. We played a few games using an ECW set by Dodo Publications, which was much simpler than the fashionable WRG set of the time and in some ways closer to the more streamlined rules popular today. The games were fun but I could find very little information about the actual battles fought between these armies. Wars between Poles and Russians, even those fought a few hundred years ago, were not a fit subject for discussion in the Polish People's Republic. Without the history to keep my interest going, the armies were packed away when I left Warsaw in 1987 and didn't come out again.

When I moved back to Poland in 2001, there was much more information generally available about all aspects of Polish history, including the Wars of the 17th century. The Military Museum in Warsaw had been refurbished and now housed an excellent section devoted to the period. The Wawel Castle museum in Kraków also has a fantastic collection of arms and armour. New books are coming out all the time, using archives that were closed for half a century.

As yet, I haven't found an English language history dealing with specific campaigns in Eastern Europe. So when arranging games with newcomers to the period I wrote introductory notes to give them a bit of background. I have drawn in these below..

Since 2001 I have been particularly interested in two mid-century conflicts: the Khmelnitzky Cossack ‘Rebellion’ against the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth and the 13 Years War between the Commonwealth and Muscovy. Specifically, I have written scenarios for the Chudniv/Cudnów campaign of 1660.

When I moved back to Poland in 2001, there was much more information generally available about all aspects of Polish history, including the Wars of the 17th century. The Military Museum in Warsaw had been refurbished and now housed an excellent section devoted to the period. The Wawel Castle museum in Kraków also has a fantastic collection of arms and armour. New books are coming out all the time, using archives that were closed for half a century.

As yet, I haven't found an English language history dealing with specific campaigns in Eastern Europe. So when arranging games with newcomers to the period I wrote introductory notes to give them a bit of background. I have drawn in these below..

Since 2001 I have been particularly interested in two mid-century conflicts: the Khmelnitzky Cossack ‘Rebellion’ against the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth and the 13 Years War between the Commonwealth and Muscovy. Specifically, I have written scenarios for the Chudniv/Cudnów campaign of 1660.

Background to the 13 Year War

The 13 Year or First Northern War began in 1654. The immediate trigger for this conflict was Moscow’s support for Khmelnytsky’s Cossack uprising against Warsaw. It was also another round in the decades-long power struggle between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Muscovy for supremacy in Eastern Europe.

Muscovy’s war aims were to reclaim lands lost to the Commonwealth earlier in the century, notably the city of Smolensk. Warsaw’s initial aim was to retain her territorial gains in the East and return the Cossacks to compliance. Within a year of the outbreak of war, her aim was simply to survive.

Those most directly involved in the war were Muscovy, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Crimean Tatars and the Cossacks. The allegiance of these last two shifted back and forth over the course of the conflict. At times there were Cossacks on both sides of the divide.

Between 1655 and 1660 both sides were preoccupied with the Swedish war, which began disastrously for Poland and brought the Commonwealth to the brink of extinction but by the Peace of Oliwa, had seen the almost total recovery of Polish political and military fortunes. Muscovy, greatly concerned by Swedish expansionism, agreed an armistice with Poland for most of this period and herself fought Swedish forces on the Baltic.

The contest resumed in 1659. The years that followed saw various changes in military fortunes and shifting alliances but neither side could deliver a knockout blow. The costs and strains of the years of conflict gradually weakened the Commonwealth and despite some notable military successes over the 13 years, it was obliged in 1667 to sign a humiliating treaty in which much land was ceded to Muscovy.

The struggle for regional predominance ended there. Muscovy would go on to become the dominant power in Eastern Europe. Commonwealth fortunes enjoyed an Indian summer later in the century under king Jan Sobieski but they never again mounted a serious challenge to Muscovy.

Over the course of the war the armies of both sides changed and evolved. The Muscovite army in particular created new formations and modified the way it fought. Contrary to some perceptions in Western Europe that still persist, the science of war in the East was neither backward nor static. Military leaders and theorists closely followed developments elsewhere on the continent. They employed west European mercenary regiments and hired experienced officers from Western Europe to train and lead their national armies. Traditional troops like the Polish Hajduks or Muscovite Streltsi appeared less and less on the battlefield, while Reiters and Pike and Shot became the backbone of many a force. Of course, Cossacks, Hussars, Tatars and the like still appeared on the battlefield but more in a secondary role. A gamer with existing Thirty Years or English Civil War armies already possesses most of the figures they will need to fight battles further to the East.

Muscovy’s war aims were to reclaim lands lost to the Commonwealth earlier in the century, notably the city of Smolensk. Warsaw’s initial aim was to retain her territorial gains in the East and return the Cossacks to compliance. Within a year of the outbreak of war, her aim was simply to survive.

Those most directly involved in the war were Muscovy, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Crimean Tatars and the Cossacks. The allegiance of these last two shifted back and forth over the course of the conflict. At times there were Cossacks on both sides of the divide.

Between 1655 and 1660 both sides were preoccupied with the Swedish war, which began disastrously for Poland and brought the Commonwealth to the brink of extinction but by the Peace of Oliwa, had seen the almost total recovery of Polish political and military fortunes. Muscovy, greatly concerned by Swedish expansionism, agreed an armistice with Poland for most of this period and herself fought Swedish forces on the Baltic.

The contest resumed in 1659. The years that followed saw various changes in military fortunes and shifting alliances but neither side could deliver a knockout blow. The costs and strains of the years of conflict gradually weakened the Commonwealth and despite some notable military successes over the 13 years, it was obliged in 1667 to sign a humiliating treaty in which much land was ceded to Muscovy.

The struggle for regional predominance ended there. Muscovy would go on to become the dominant power in Eastern Europe. Commonwealth fortunes enjoyed an Indian summer later in the century under king Jan Sobieski but they never again mounted a serious challenge to Muscovy.

Over the course of the war the armies of both sides changed and evolved. The Muscovite army in particular created new formations and modified the way it fought. Contrary to some perceptions in Western Europe that still persist, the science of war in the East was neither backward nor static. Military leaders and theorists closely followed developments elsewhere on the continent. They employed west European mercenary regiments and hired experienced officers from Western Europe to train and lead their national armies. Traditional troops like the Polish Hajduks or Muscovite Streltsi appeared less and less on the battlefield, while Reiters and Pike and Shot became the backbone of many a force. Of course, Cossacks, Hussars, Tatars and the like still appeared on the battlefield but more in a secondary role. A gamer with existing Thirty Years or English Civil War armies already possesses most of the figures they will need to fight battles further to the East.

Sources

The first useful source about this campaign is Wikipedia, in both English and Polish. The Polish entries tend to be fuller than the English ones but the English entries will still provide an overview.

I also used three other sources, all in Polish:

Łukasz Ossoliński, Cudnów – Słobodyszcze 1660, Zabrze Inforteditions 2006, ISBN 83-89943-12-3

Romuald Romański, Cudnów 1660, Warszawa Bellona 1996, ISBN 83-11-08590-0.

Radosław Sikora, Rekordowa szarża? Kutyszcze 26 IX 1660. „Niezwykłe bitwy i szarże husarii”. Warszawa 2011.

I found Romanski easiest to read but Ossolinski gave more of the sort of detail that helps to set up a wargame. I decided to use his orders of battle. Sikora writes about one incident in the campaign that explores the effectiveness of the Polish Hussar, a warrior class already declining in numbers by 1660. If you Google Sikora you will find various articles he wrote about the period and especially about the winged hussar.

I'm not aware of any translations of these sources into English although I believe a few of Sikora's more general articles about the Hussar have been translated.

I also used three other sources, all in Polish:

Łukasz Ossoliński, Cudnów – Słobodyszcze 1660, Zabrze Inforteditions 2006, ISBN 83-89943-12-3

Romuald Romański, Cudnów 1660, Warszawa Bellona 1996, ISBN 83-11-08590-0.

Radosław Sikora, Rekordowa szarża? Kutyszcze 26 IX 1660. „Niezwykłe bitwy i szarże husarii”. Warszawa 2011.

I found Romanski easiest to read but Ossolinski gave more of the sort of detail that helps to set up a wargame. I decided to use his orders of battle. Sikora writes about one incident in the campaign that explores the effectiveness of the Polish Hussar, a warrior class already declining in numbers by 1660. If you Google Sikora you will find various articles he wrote about the period and especially about the winged hussar.

I'm not aware of any translations of these sources into English although I believe a few of Sikora's more general articles about the Hussar have been translated.

The campaign in Ukraine, 1660

The year 1660 during the 13 Years War saw major Muscovite initiatives in both Belarus/Lithuania and Ukraine. The Ukrainian campaign in particular offers some interesting scenario inspiration.

As sometimes happened in this region and period, the campaigning season in Ukraine started late, partly to avoid the heat of summer and partly because it took time for armies to muster across the great distances involved. Sheremetyev, Russian Voivod of Kiev, gathered his Muscovite-Cossack army at Kotelnia while his Cossack ally, Yurii Khmelnytsky, raised his standard at Korsun. The Poles, meanwhile, were mustering in Tarnopol, where they were to rendezvous with the Crimean Tatars. The Muscovite campaign objective was to defeat the Polish army of Grand Hetman Potocki, take Lviv and, if time allowed, threaten Krakow. Sheremetyev was confident that his army both outnumbered the Poles (by as much as 100%, so he believed) and was at least their equal in quality.

In early September 1660 Sheremetyev began his march towards Tarnopol, leaving a forward supply base in the city of Chudnov. At dusk on 14 September, a day’s march from there, his vanguard was attacked by Tatar horsemen as it left the forest on the approaches to the town of Lubar. Sheremetyev's troops were taken by surprise. He had not deployed scouts ahead of his army because he believed the Poles to be several days' march away. In fact Potocki had been advancing Eastwards and had reached Lubar with his mounted troops in the course of the 14th. Although his infantry and artillery were still en route, Potocki decided to press the advantage of surprise and attack with cavalry and dragoons. Sheremetyev's vanguard, composed of Cossack troops, recovered quickly from the surprise and occupied high ground beyond the forest edge. After a stand-off between the Poles and Cossacks, Muscovite horse eventually arrived from further down the column. and Potocki's troops withdrew as night fell. The first encounter had been a stalemate.

Overnight on the 14th the Voivod's whole army arrived on the high ground above Lubar. On the 15th Sheremetyev drew up in Battle array before his camp while infantry and labourers fortified it with entrenchments (standard practice at this time). All he faced were more Tatars and Polish Light Horse, who made reconnaissance difficult. However a Polish Cossack who deserted during the day reported that Potocki and Gierey Sultan had believed that Sheremetyev had not begun campaigning and that they had been advancing to Chudnov to establish a forward base. They had been totally surprised to encounter the Muscovite army and were now in disagreement whether to face him or retreat.

At a Council of War on the evening of the 15th Sheremetyev agreed with Tsetsura, leader of his attached Cossack contingent, that they would seek a decisive battle the next day, 16 September.

Unfortunately for Sheremetyev, the real situation was very different. Hetman Potocki had spies throughout the Muscovite camp and was well aware of their strength and plans. The Cossack ''deserter' had been a plant, sent to mislead Sheremetyev as to Commonwealth strengths and intentions. Conversely Potocki's light cavalry strength was so much greater and more able than the enemy that he had been able to mask an important reinforcement that transformed the balance of forces. Unknown to Sheremetyev, Field Hetman Lubomirski and his forces had left the Baltic and joined Potocki, bringing the Commonwealth army to parity with the enemy and giving Potocki a particular superiority in cavalry.

Potocki and Lubomirski were keen to meet and defeat Sheremetyev in pitched battle, knowing that if he found out about their increased strength, he may well take refuge in his camp and wait for Khmelnytsky to reinforce him. Accounts differ over who advocated what plan. The version derived from Lubomirski's memoirs seems to be that Lubomirski advocated hiding his strength until the Muscovites were too committed to the battle to withdraw. Potocki, allegedly, was less interested in a cunning plan and wanted to deploy the combined armies together from the outset. Whether or not the two hetmen had different ideas about how to conduct the battle, they failed to defeat the enemy in the open. There was hard fighting on both flanks: on the Muscovite left, a fortified hill that covered the front of Sheremetyev’s camp changed hand several times; while Tsetsura’s Cossacks fought first Tatars and then Polish Infantry in the woods and rough ground to the West of their camp. However there was no meeting of the two centres. The Polish story goes that Sheremetyev realised soon after starting the engagement that his enemy had been reinforced. He therefore broke off the battle and withdrew into his entrenchments, to await the arrival of Khmelnytsky. The Commonwealth army settled down to besiege the Muscovite camp.

There is another version of the decisions of 16 September, more favourable to Sheremetyev. This is that he planned all along to make a demonstration in the open in order to draw the Poles onto his entrenchments. Having done so, he withdrew into his camp hoping that the Poles would waste men trying to break into his fortified position. His ruse nearly worked as by dusk, Polish foot had occupied the Cossack trenches and were only recalled by Lubomirski who did not want to become further embroiled in the enemy’s fortifications.

While waiting for Khmelnitsky, Sheremetyev had to deal with two problems. First, the camp at Lubar was badly situated and the fodder and water supply was poor. Second, his Cossack ally seemed in no hurry to come to his aid. Increasingly unhappy with his position at Lubar, the Voivod decided to retreat to his supply depot at Chudnov, where he could bring his army closer to the advancing Cossack allies and make camp in a better location. On 26 September Sheremetyev abandoned Lubar and retired to Chudnov,. In pursuit, Potocki inflicted a reverse on the Muscovites as they crossed the River Ibr, but could not stop them from reoccupying Chudnov. Once again, Potocki laid siege to the Muscovite camp. There followed various skirmishes between the two armies but no major engagement occurred.

In early October news reached Potocki that Khmelnitsky was finally approaching and that the Polish camp was between the Muscovites and the advancing Cossack army. In response he shifted the Commonwealth camp into a more defensible position and despatched a strike force under Lubomirski to intercept Khmelnitsky. Lubomorski encountered the Cossack Army in camp at Slobodyszcze on 7 October and attacked immediately.

The battle of Slobodyszcze saw a numerically inferior but highly motivated Commonwealth force attack uphill against a mostly unprepared Cossack camp. Accounts of the battle vary widely, with some Russian historians even claiming that no real battle took place at all: they suggest that Khmelnytsky had already resolved to make peace with the Comminwealth and that he made no more than a token display of aggression for the sake of appearances. Polish and Ukrainian historians maintain that a real battle did take place, in which initial Commonwealth success in storming the Cossack camp was blunted by a successful counterattack, resulting in a stalemate by the end of the day. Thereafter however peace feelers were sent out and Khmelnytsky and Lubomirski negotiated a ceasefire. This left Sheremetyev in a most uncomfortable situation at Chudnov, with no hope of reinforcement and a sizeable Cossack contingent whose loyalty was now in doubt.

The elimination of Khmelnytsky marked the beginning of the end for Sheremetyev. Conditions in his camp deteriorated and desertions increased. Potocki meanwhile. kept up the pressure of the siege. There were some desperate attempts to break through the Comonwealth blockade, but none succeeded. Finally, in early November Sheremetyev marched his army into captivity.. A great many of his men were taken by the Tatars, where they were sold into slavery. Sheremetyev himself spent the rest of his life in captivity. This was the most complete victory for the Commonwealth in the whole war.

As sometimes happened in this region and period, the campaigning season in Ukraine started late, partly to avoid the heat of summer and partly because it took time for armies to muster across the great distances involved. Sheremetyev, Russian Voivod of Kiev, gathered his Muscovite-Cossack army at Kotelnia while his Cossack ally, Yurii Khmelnytsky, raised his standard at Korsun. The Poles, meanwhile, were mustering in Tarnopol, where they were to rendezvous with the Crimean Tatars. The Muscovite campaign objective was to defeat the Polish army of Grand Hetman Potocki, take Lviv and, if time allowed, threaten Krakow. Sheremetyev was confident that his army both outnumbered the Poles (by as much as 100%, so he believed) and was at least their equal in quality.

In early September 1660 Sheremetyev began his march towards Tarnopol, leaving a forward supply base in the city of Chudnov. At dusk on 14 September, a day’s march from there, his vanguard was attacked by Tatar horsemen as it left the forest on the approaches to the town of Lubar. Sheremetyev's troops were taken by surprise. He had not deployed scouts ahead of his army because he believed the Poles to be several days' march away. In fact Potocki had been advancing Eastwards and had reached Lubar with his mounted troops in the course of the 14th. Although his infantry and artillery were still en route, Potocki decided to press the advantage of surprise and attack with cavalry and dragoons. Sheremetyev's vanguard, composed of Cossack troops, recovered quickly from the surprise and occupied high ground beyond the forest edge. After a stand-off between the Poles and Cossacks, Muscovite horse eventually arrived from further down the column. and Potocki's troops withdrew as night fell. The first encounter had been a stalemate.

Overnight on the 14th the Voivod's whole army arrived on the high ground above Lubar. On the 15th Sheremetyev drew up in Battle array before his camp while infantry and labourers fortified it with entrenchments (standard practice at this time). All he faced were more Tatars and Polish Light Horse, who made reconnaissance difficult. However a Polish Cossack who deserted during the day reported that Potocki and Gierey Sultan had believed that Sheremetyev had not begun campaigning and that they had been advancing to Chudnov to establish a forward base. They had been totally surprised to encounter the Muscovite army and were now in disagreement whether to face him or retreat.

At a Council of War on the evening of the 15th Sheremetyev agreed with Tsetsura, leader of his attached Cossack contingent, that they would seek a decisive battle the next day, 16 September.

Unfortunately for Sheremetyev, the real situation was very different. Hetman Potocki had spies throughout the Muscovite camp and was well aware of their strength and plans. The Cossack ''deserter' had been a plant, sent to mislead Sheremetyev as to Commonwealth strengths and intentions. Conversely Potocki's light cavalry strength was so much greater and more able than the enemy that he had been able to mask an important reinforcement that transformed the balance of forces. Unknown to Sheremetyev, Field Hetman Lubomirski and his forces had left the Baltic and joined Potocki, bringing the Commonwealth army to parity with the enemy and giving Potocki a particular superiority in cavalry.

Potocki and Lubomirski were keen to meet and defeat Sheremetyev in pitched battle, knowing that if he found out about their increased strength, he may well take refuge in his camp and wait for Khmelnytsky to reinforce him. Accounts differ over who advocated what plan. The version derived from Lubomirski's memoirs seems to be that Lubomirski advocated hiding his strength until the Muscovites were too committed to the battle to withdraw. Potocki, allegedly, was less interested in a cunning plan and wanted to deploy the combined armies together from the outset. Whether or not the two hetmen had different ideas about how to conduct the battle, they failed to defeat the enemy in the open. There was hard fighting on both flanks: on the Muscovite left, a fortified hill that covered the front of Sheremetyev’s camp changed hand several times; while Tsetsura’s Cossacks fought first Tatars and then Polish Infantry in the woods and rough ground to the West of their camp. However there was no meeting of the two centres. The Polish story goes that Sheremetyev realised soon after starting the engagement that his enemy had been reinforced. He therefore broke off the battle and withdrew into his entrenchments, to await the arrival of Khmelnytsky. The Commonwealth army settled down to besiege the Muscovite camp.

There is another version of the decisions of 16 September, more favourable to Sheremetyev. This is that he planned all along to make a demonstration in the open in order to draw the Poles onto his entrenchments. Having done so, he withdrew into his camp hoping that the Poles would waste men trying to break into his fortified position. His ruse nearly worked as by dusk, Polish foot had occupied the Cossack trenches and were only recalled by Lubomirski who did not want to become further embroiled in the enemy’s fortifications.

While waiting for Khmelnitsky, Sheremetyev had to deal with two problems. First, the camp at Lubar was badly situated and the fodder and water supply was poor. Second, his Cossack ally seemed in no hurry to come to his aid. Increasingly unhappy with his position at Lubar, the Voivod decided to retreat to his supply depot at Chudnov, where he could bring his army closer to the advancing Cossack allies and make camp in a better location. On 26 September Sheremetyev abandoned Lubar and retired to Chudnov,. In pursuit, Potocki inflicted a reverse on the Muscovites as they crossed the River Ibr, but could not stop them from reoccupying Chudnov. Once again, Potocki laid siege to the Muscovite camp. There followed various skirmishes between the two armies but no major engagement occurred.

In early October news reached Potocki that Khmelnitsky was finally approaching and that the Polish camp was between the Muscovites and the advancing Cossack army. In response he shifted the Commonwealth camp into a more defensible position and despatched a strike force under Lubomirski to intercept Khmelnitsky. Lubomorski encountered the Cossack Army in camp at Slobodyszcze on 7 October and attacked immediately.

The battle of Slobodyszcze saw a numerically inferior but highly motivated Commonwealth force attack uphill against a mostly unprepared Cossack camp. Accounts of the battle vary widely, with some Russian historians even claiming that no real battle took place at all: they suggest that Khmelnytsky had already resolved to make peace with the Comminwealth and that he made no more than a token display of aggression for the sake of appearances. Polish and Ukrainian historians maintain that a real battle did take place, in which initial Commonwealth success in storming the Cossack camp was blunted by a successful counterattack, resulting in a stalemate by the end of the day. Thereafter however peace feelers were sent out and Khmelnytsky and Lubomirski negotiated a ceasefire. This left Sheremetyev in a most uncomfortable situation at Chudnov, with no hope of reinforcement and a sizeable Cossack contingent whose loyalty was now in doubt.

The elimination of Khmelnytsky marked the beginning of the end for Sheremetyev. Conditions in his camp deteriorated and desertions increased. Potocki meanwhile. kept up the pressure of the siege. There were some desperate attempts to break through the Comonwealth blockade, but none succeeded. Finally, in early November Sheremetyev marched his army into captivity.. A great many of his men were taken by the Tatars, where they were sold into slavery. Sheremetyev himself spent the rest of his life in captivity. This was the most complete victory for the Commonwealth in the whole war.

What rules to use?

It took me a long time to find a rule set that both covered all the relevant troop types for this theatre and was fun to play. The Dodo ECW rules that I bought in the 1980s were my favourite for a long time. I found the WRG Renaissance rules too much of a slog. I bought Fields of Glory Renaissance having read that these play better than FOG Ancients, and they may very well do. However I could never get around to trying them. I don’t quite know what will persuade me to try out a set of rules: for every set I play, I must have three or four that just sit on the bookshelf.

In the 2000s there was a flurry of new rule sets for the late Renaissance/ECW. The first I picked up was Pike and Shotte by Warlord. There were gaps in the army stats provided in the main rulebook but we filled them using the attributes in the rulebook. We played some great games with Pike and Shotte but one of our players lost a game after a string of poor command rolls and took against them, so they were put to one side. I will bring them out again some time.

The next rules to try were Tercios and the supplement, Kingdoms, by the Spanish company El Kraken. I really like the mechanisms and we have played some exciting games, but the order system make them a bit heavy going for larger actions. Definitely a set to keep playing for small and medium actions..

Then along came For King and Parliament by Big Red Bat Ventures. Perfect for bigger battles, original and elegant, I have been trying amendments for eastern armies, borrowing mechanisms from the parent rules, To the Strongest. So far, they are looking promising.

There are various entries on the blog about testing and playing with Tercios and with For King and Parliament.

In the 2000s there was a flurry of new rule sets for the late Renaissance/ECW. The first I picked up was Pike and Shotte by Warlord. There were gaps in the army stats provided in the main rulebook but we filled them using the attributes in the rulebook. We played some great games with Pike and Shotte but one of our players lost a game after a string of poor command rolls and took against them, so they were put to one side. I will bring them out again some time.

The next rules to try were Tercios and the supplement, Kingdoms, by the Spanish company El Kraken. I really like the mechanisms and we have played some exciting games, but the order system make them a bit heavy going for larger actions. Definitely a set to keep playing for small and medium actions..

Then along came For King and Parliament by Big Red Bat Ventures. Perfect for bigger battles, original and elegant, I have been trying amendments for eastern armies, borrowing mechanisms from the parent rules, To the Strongest. So far, they are looking promising.

There are various entries on the blog about testing and playing with Tercios and with For King and Parliament.

Turning Orders of Battle into wargames armies

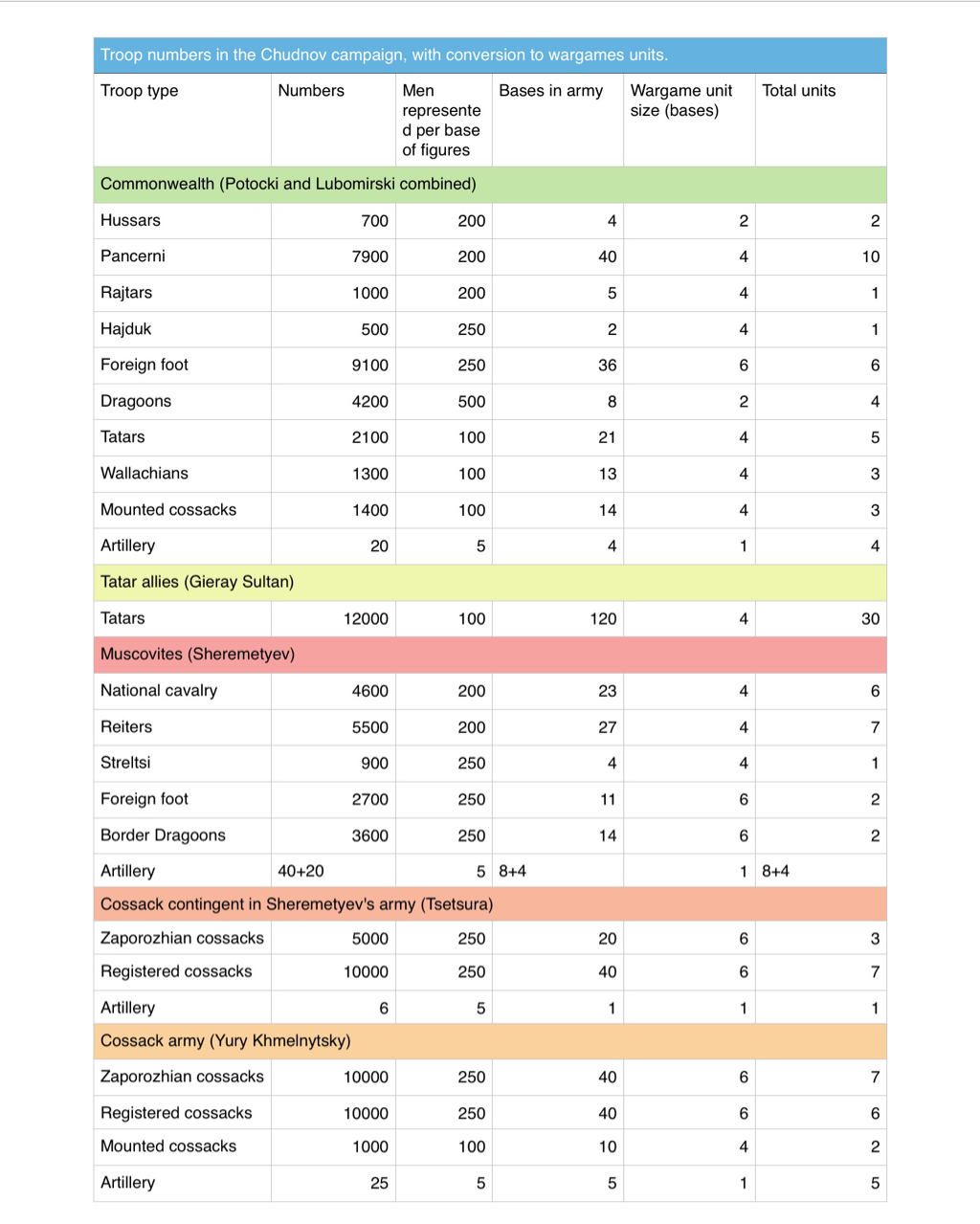

Version one: for Pike and Shotte

There are differing versions of the troop numbers involved in the 1660 Campaign. Strength returns were infrequent and inaccurate. Estimates of enemy numbers could go way off as both sides tended to inflate their opponent's strength, either to help excuse defeat or to make their own success the more impressive. Non combatants could also be included in overall totals. From the sources available to me, I went with Ossolinski, who generally argues for the lower numbers in all of the armies involved. I put these into a table, with the overall numbers for each troop type present. To convert these numbers into wargames units, I worked out how many men each base of figures represented and calculated how many bases of each troop type were in the army. In the army lists for FIelds of Glory Renaissance, unit sizes came down to 4 cavalry or 6 infantry stands for a standard size unit, and 2 cavalry or 4 infantry for a small one. I divided the total number of bases of each troop type by these unit sizes to determine how many units (and of what size) would be needed to represent each category. This calculation resulted in 41 units in the Muscovite main army and 39 in the Commonwealth, which was too many for me to represent on the table. However, by halving these totals, I came almost exactly to the size of my current collection. I was mostly able to retain the historical ratios between the different categories, with a few exceptions for small contingents like Hajduks, Streltsi and, indeed, Polish hussars. I represented these troop types as small units but even so, their numbers were exaggerated. Overall, I ended up with wargames armies that reflected the composition of the real armies pretty well. See the table below.

Notes:

The foreign regiments in the Commonwealth army were equipped in West European style and often had foreign officers, but many of the troops were actually Polish. This group includes the Royal Guard Foot regiment.

The Muscovite border dragoons were poorly mounted if at all and behaved on the battlefield like infantry rather than dragoons.

There are two types of Cossack foot in the list, Zaporozhian and Registered. The former represent those units raised during the rebellion, while the latter represent regiments, previously in Commonwealth pay, that deserted their employer when the Khmelnytsky rebellion began. Registered Cossacks were better trained and dressed than the newly raised Zaporozhians (their payment had partly been in cloth for uniforms). However the distinctions between their fighting abilities are not pronounced: many in the Zaporozhian regiments had previously served in Polish pay. The ratio of these two groups to one another in the wargames armies is arbitrary: I can't find a source that explains how many of each were represented.

Every army had a large tail of vehicles, or Tabor, essential for keeping it supplied in the often barren wildernesses of Eastern Europe. The Cossacks in particular were renowned for using their Tabor in line of battle. These were simply peasant vehicles, not purpose-built war wagons, but they provided vital cover from enemy Horse. When encamped, wagons could be incorporated in the earthworks. On the move, wagons were sometimes formed up in dense blocks, like a slow moving fortress. Light artillery could be mounted on them. It is difficult to set a figure for the total number of wagons that might find themselves in the line of battle. I decide the total according to the battle and if the scenario requires Cossacks to be defending wagons, I swap two wagon models for each 6-stand regiment of Cossacks. I also use two sets of statistics for wagons, depending whether they are moving or incorporated in a prepared defensive position. In the latter case, drought horses would have been removed and earth banked up under the axles of the wagon.

Unit statistics for all these troop types are in a PDF file in the Scenarios section.

The foreign regiments in the Commonwealth army were equipped in West European style and often had foreign officers, but many of the troops were actually Polish. This group includes the Royal Guard Foot regiment.

The Muscovite border dragoons were poorly mounted if at all and behaved on the battlefield like infantry rather than dragoons.

There are two types of Cossack foot in the list, Zaporozhian and Registered. The former represent those units raised during the rebellion, while the latter represent regiments, previously in Commonwealth pay, that deserted their employer when the Khmelnytsky rebellion began. Registered Cossacks were better trained and dressed than the newly raised Zaporozhians (their payment had partly been in cloth for uniforms). However the distinctions between their fighting abilities are not pronounced: many in the Zaporozhian regiments had previously served in Polish pay. The ratio of these two groups to one another in the wargames armies is arbitrary: I can't find a source that explains how many of each were represented.

Every army had a large tail of vehicles, or Tabor, essential for keeping it supplied in the often barren wildernesses of Eastern Europe. The Cossacks in particular were renowned for using their Tabor in line of battle. These were simply peasant vehicles, not purpose-built war wagons, but they provided vital cover from enemy Horse. When encamped, wagons could be incorporated in the earthworks. On the move, wagons were sometimes formed up in dense blocks, like a slow moving fortress. Light artillery could be mounted on them. It is difficult to set a figure for the total number of wagons that might find themselves in the line of battle. I decide the total according to the battle and if the scenario requires Cossacks to be defending wagons, I swap two wagon models for each 6-stand regiment of Cossacks. I also use two sets of statistics for wagons, depending whether they are moving or incorporated in a prepared defensive position. In the latter case, drought horses would have been removed and earth banked up under the axles of the wagon.

Unit statistics for all these troop types are in a PDF file in the Scenarios section.

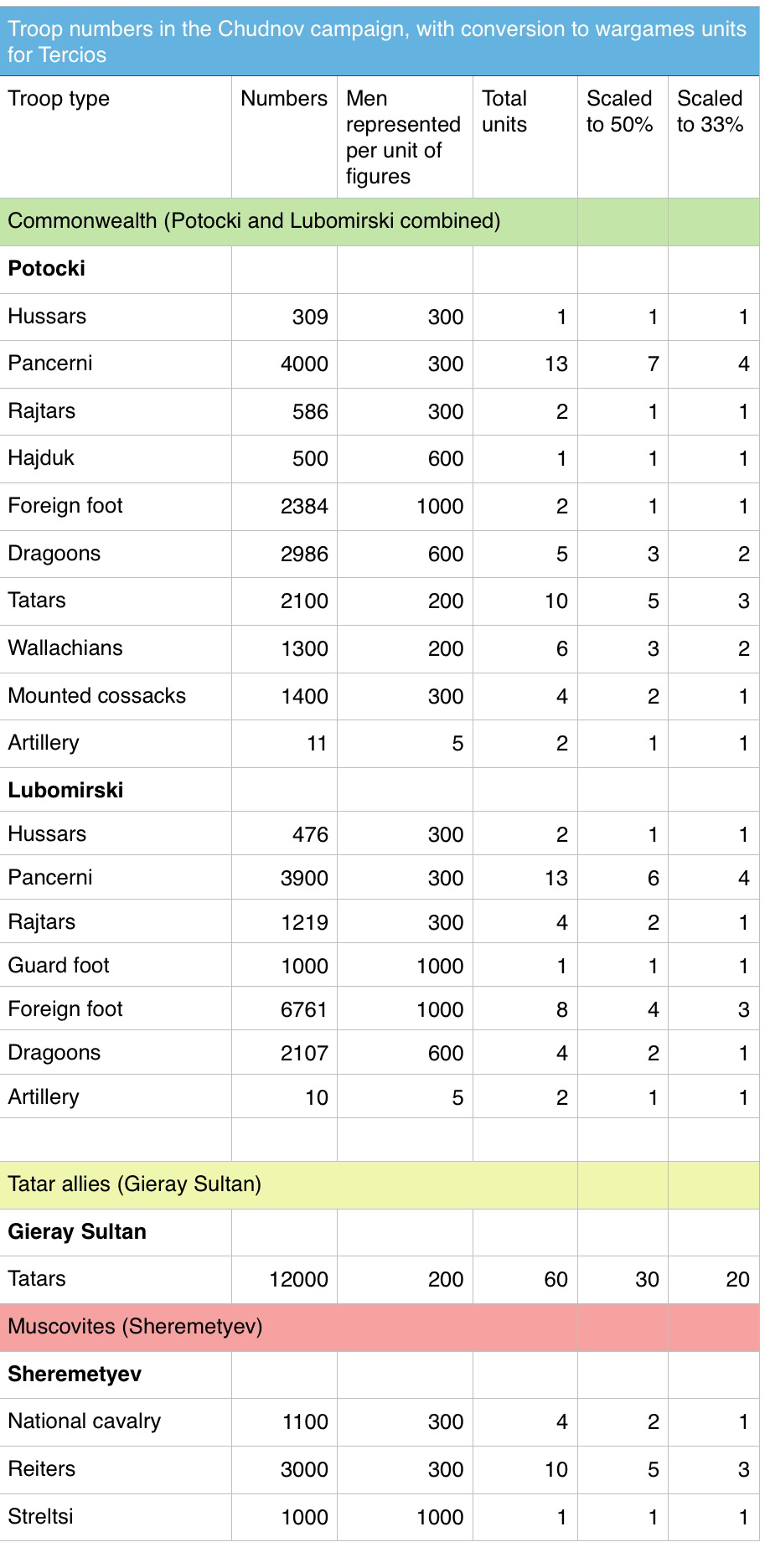

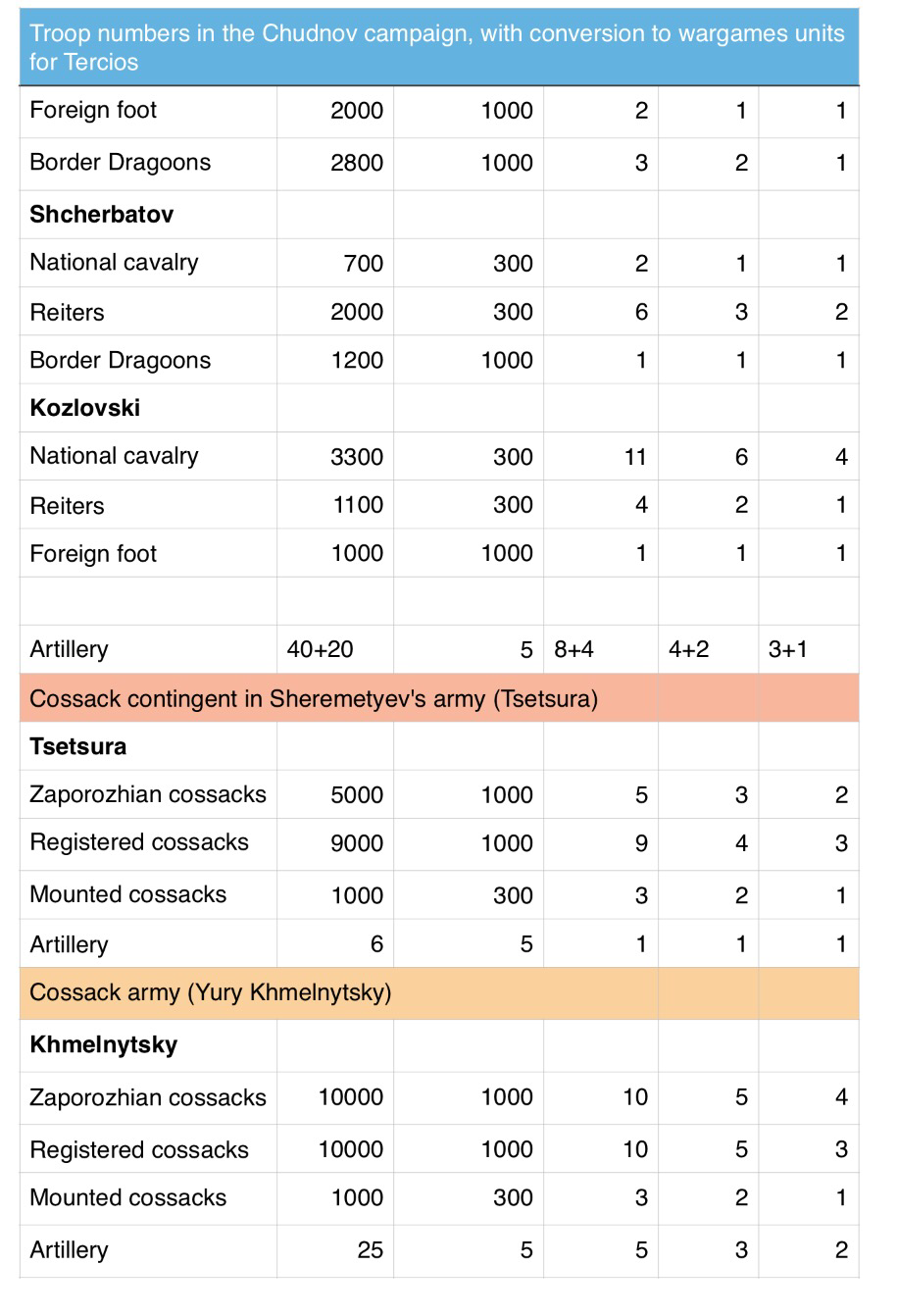

Version two: for Tercios

I have also had a go at adapting the 1660 Orbat for the rules set Tercios. The rules count whole units of either 80 or 120mm frontage. They don't provide a figure to man scale, which is a bit frustrating but seems to be the fashion these days. So I have made my own attempt at calculating unit sizes. As with Pike and Shotte, a straight conversion gives far more units than I possess, but by dividing the total by 50 and by 33%, I came closer to what is achievable while broadly reflecting the ratios in the historical armies. As before, the Hussars are over represented in the 50 and 33% forces, but I would still represent these as two small units.

Scenarios for the campaign of 1660

First contact in Ukraine, 14 September 1660

The first scenario represents the initial contact on 14 September between Sheremetyev's vanguard and Potocki's cavalry and Tatar allies. I wrote this as a scenario for Sam Mustafa's Maurice rules. These rules are intended for 18th century warfare but include rules for pike and shot regiments. I like the elegant and characterful mechanics of Sam's games, and wanted to see how they felt with these armies. After some reflection, I decided to allow bow-armed light cavalry to fire, at a reduced effect compared to foot, but without firepower, it would be very difficult to reflect the way Tatars in particular fought. I did not give firepower to bow- or pistol-armed regular cavalry, however: the sources I have read suggest that by now, all formed cavalry, including Reiters, closed with the sword rather than fire from the saddle. For Polish dragoons, I followed advice on the Maurice forum to portray them as irregular infantry. This makes them more nimble than regulars, but less effective in volley fire or combat. It makes sense to consider them dismounted before battle begins. Their horses allowed them to keep pace with the cavalry on the march, but I can't find any account of dragoons at this period operating mounted in the presence of the enemy. We are playing the scenario on 9 January. I have posted a PDF of the scenario on the Scenarios page.