|

I’ve been down another rabbit hole recently, reading up about Poles in the Napoleonic era for a Sharp Practice game about the death of Poniatowski. There is an excellent facebook group called “Epoka Napoleońska”, which often posts albums of uniforms and battle scenes from the period. Recently this group posted a link to an article from the Polish magazine “Historia”, published on 27 February 2023, about the origins of the Polish national anthem. It was so interesting that I decided to summarise it here. The story begins with the Third Partition in 1795, when the Polish State disappeared from the map, her territories shared out between Russia, Austria and Prussia. In 1797 the Polish Legions were raised in Italy under French sponsorship, attracting former soldiers and young patriots in exile. Their commander was General Jan Henryk Dąbrowski, an experienced officer who would serve the Polish cause throughout the Napoleonic wars. Also in 1797, the Polish nobleman, politician and writer, Józef Wybicki, a friend of Dąbrowski who had joined him in Italy, wrote a poem that became known as “the Song of the Polish Legions in Italy”. The words were set to the music of a popular Mazurka and sung for the first time on 20 July 1797 in Reggio Emilia in Italy. The Dąbrowski’s Mazurka soon became the Legions’ marching song and its popularity spread. In 1806 it was first printed in the partitioned Polish territories, and from then on, it became an enduring symbol of the ambition to regain independence. Despite being banned by the partitioning powers, the song kept its popularity and eventually became the official national anthem of the restituted Poland in 1927. The loyalty and courage of Polish troops in Napoleon’s service is legendary. The words of Dąbrowski’s Mazurka help demonstrate how tightly the dream of restored nationhood was bound to the person of the French Emperor. Small wonder they fought so hard for him, right up to the end. The original song had six verses, though verses four and six have been dropped in modern times (you can guess why) . Some of the words have changed slightly since 1797 but the gist is exactly the same. My loose translation is below Poland has not yet died As long as we are alive We shall take back by the sword What foreign powers have stolen. Refrain: March, march, Dąbrowski From Italian lands to Poland Under your command We shall unite with the nation. We will cross the Vistula, cross the Warta We will be Poles Bonaparte has shown us by example How we shall be victorious. Refrain Just as Czarniecki returned to Poznan From across the sea To save the fatherland After the Swedish partition. Refrain Neither German nor Muscovite shall settle (our lands) When, having drawn our sword, Our watchword will be “Unity And our Fatherland”. Refrain So the father says To his weeping (daughter) Basia “Hark! It seems our (lads) Are beating the military drums”. Refrain At this we all say with one voice “Enough of this captivity! We have the scythes of Racławice Kościuszko, if God wills it”. And the Polish original text: Jeszcze Polska nie umarła,

Kiedy my żyjemy. Co nam obca moc wzięła, Szablą odbierzemy. Refrain: Marsz, marsz, Dąbrowski —Do Polski z ziemi włoski —Za twoim przewodem —Złączym się z narodem. Przejdziem Wisłę, przejdziem Wartę Będziem Polakami Dał nam przykład Bonaparte Jak zwyciężać mamy. Refrain Jak Czarniecki do Poznania Wracał się przez morze Dla ojczyzny ratowania Po szwedzkim rozbiorze. Refrain Niemiec, Moskal nie osiędzie, Gdy jąwszy pałasza, Hasłem wszystkich zgoda będzie I ojczyzna nasza. Refrain Już tam ojciec do swej Basi Mówi zapłakany Słuchaj jeno, pono nasi Biją w tarabany. Refrain Na to wszystkich jedne głosy Dosyć tej niewoli Mamy racławickie kosy Kościuszkę Bóg pozwoli. Refrain

0 Comments

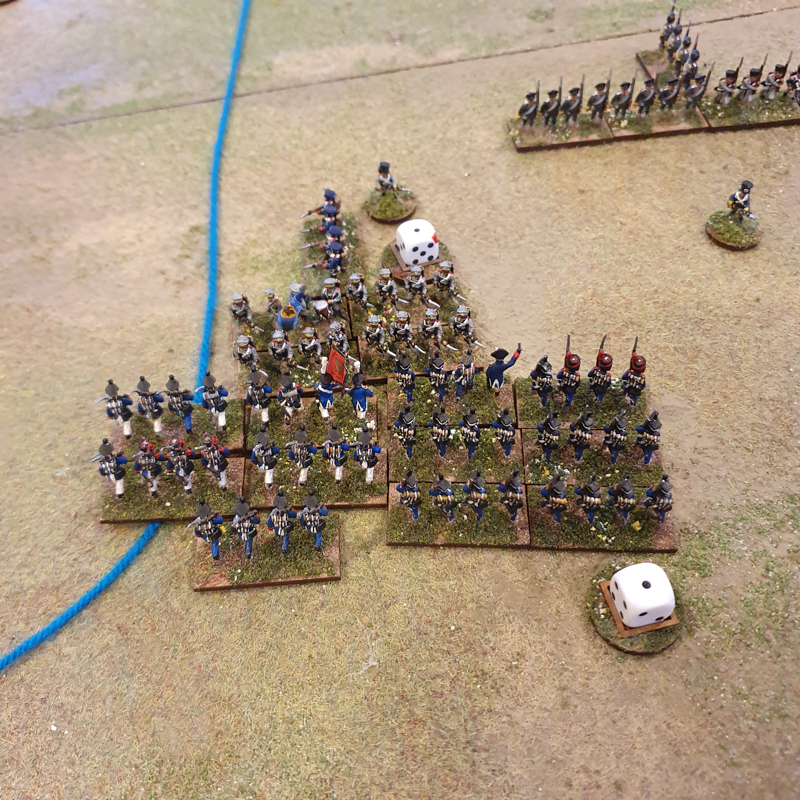

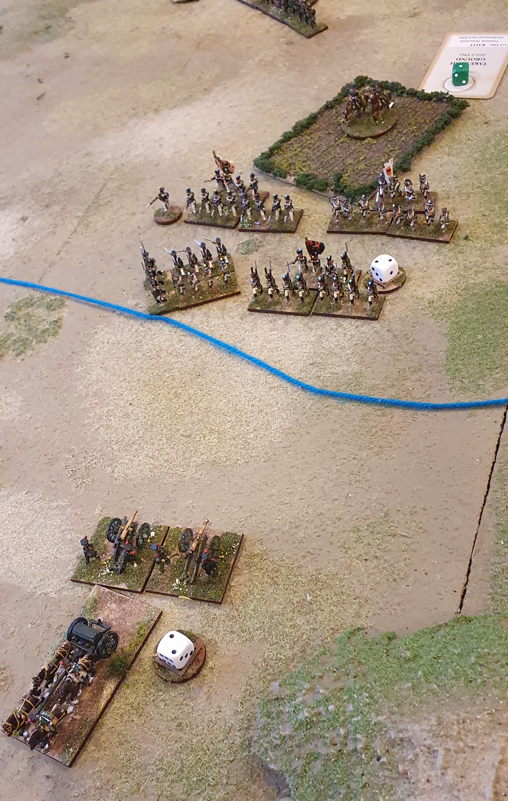

I have been gathering ideas for a Sharp Practice scenario of the last moments of Prince Józef Poniatowski, Commander in Chief of the army of the Duchy of Warsaw, who died on the last day of the battle of Leipzig in October 1813. I found two accounts in Polish, one by Mariusz Lukasiewicz in his book “Armia Ksiecia Jozefa, 1813” and the other in “Lipsk”, by Jadwiga Nadzieja. Both accounts drew on eye witness reports and are almost identical. The following is a translation of the account in Lukasiewicz, with a small comment from Nadzieja’s book. Introduction: On 19 October 1813, Napoleon’s army was retreating westwards from Leipzig, covered by a rearguard including Poniatowski’s Polish VIII Corps. The army had only one route out of the city and while the details are still disputed, the single bridge over which the troops were retreating was blown up prematurely, leaving several thousand troops of the rearguard on the far side, including the Poles. With the bridge gone, the only way the stranded troops could avoid death or capture was to cross two rivers, the Pleisse and then the Elster, either on makeshift bridges or by swimming. Meanwhile, Russian and Prussian skirmishers were racing to cut them off. “Poniatowski retreated from the water fountain, together with his headquarters staff and remaining soldiers. They moved through the Reichel‘s garden and the Rudolf garden towards the river Pleisse under fire from approaching enemy skirmishers. The cuirassiers and some chasseurs were still fighting. General Bronikowski strongly urged the commander-in-chief to swim his horse across the Pleisse. Poniatowski was reluctant to withdraw, but eventually ordered his escort to gain time with one more charge and then jumped into the river. The Pleisse was deep and fast moving due to the autumn rains and Poniatowski’s horse couldn’t make it up the far bank. Seeing him in trouble Hypolite Blechamps, a young French captain on the Headquarters staff, ran to help. (Jadwiga Nadzieja says he was assisted by another aide, Ludwig Kicki, who was shot soon after dragging Poniatowski to the bank). He freed Poniatowski from his horse and pulled him onto the riverbank. The prince now proceeded for a time on foot. As he retreated through the gardens he was wounded for a fourth time, this time by a musket ball in his side. The wound was serious and only quick attention stopped him from bleeding to death. Poniatowski fell unconscious into the arms of his escort but soon regained his senses. His staff begged him to hand over command to one of his generals and surrender to the Allies so his wounds could be properly treated. Now half-conscious, Poniatowski refused, saying that his honour and duty to his Fatherland would not permit him to do this. With the help of his adjutants, he mounted another horse and supported from both sides, rode along the River Elster towards a crossing place that had been indicated by an officer of engineers. Allied troops had by now already reached the river and some had even crossed to the other side, shooting at the soldiers as they tried to swim to safety. Bleeding heavily and losing consciousness every few moments Poniatowski’s path was suddenly blocked by an enemy detachment and he turned his horse and jumped in the river. The horse managed with difficulty to reach the far bank, but as it scrambled to get out of the water, Poniatowski was hit again by a musket ball. He slid off the horse into the water and began to drown. Captain Blechamps again jumped in to help him, but soon they both disappeared in the current and neither was seen alive again. Poniatowski’s corpse was recovered from the Elster by a local fisherman on 24 October and his identity confirmed by Polish prisoners.” On 10 September, my friend Keith came up from Devon to attend Colours at Newbury and then play a game of Soldiers of Napoleon. We played the Ligny scenario mentioned in my last blog post, on the Napoleonic scenarios page here. On 26 September, Dan, Spencer and I played the scenario again. They were both cracking games. Skip this bit if you already play SoNAs Soldiers of Napoleon (SoN) is still a new set, it might be worth summarising the way the rules work. The USP is the deck of cards, which regulate various aspects of play. The players start the turn with a hand of cards each, which they play alternately until both run out and the turn finishes. Each card can be played for one of three purposes: to issue orders to a variable number of units in one brigade; to rally all eligible units in a brigade; or to launch a special event. Of course, you can’t use a card for more than one purpose at a time so there are always tough choices to be made. Movement and shooting are both straightforward processes, in much the same mould as other Napoleonic rules. There are a couple of unusual orders that we really like: light cavalry can ‘harass’ enemy skirmishers, with the possible result that the skirmishers will fall back to rejoin their parent battalions. Heavy cavalry, meanwhile, can intimidate enemy by their very presence. I like it that your cavalry can influence the battle in more subtle ways than charging at the first target. The rally and stand removal mechanic is highly original and takes some getting used to. An important point to remember is that while every card has a Rally function, you can only rally troops of the quality levels specified on that card. Pretty much every card lets you rally elite and professional troops but very few cards allow you to rally militia. So if, like the Prussians in 1815, you have a lot of Landwehr militia in your army, make every card that can be used to rally militia count. Sadly, this will mean forgoing some neat special events and high digit orders, but your army will dissolve if you don’t rally your militia when you can. The Rally process involves different steps that it is important to follow in sequence. You can soak off disruption points in different ways including stand removal. While stand removal is seemingly voluntary, it is better to lose a stand or two in a rally action than to lose the whole unit at turn’s end because it had more disruption points than stands remaining. Anyway, we were both set up and ready to go. The First Game beginsIn game 1, Keith took Girard’s 7th Division, holding St Amand La Haye, while I led the Prussians, tasked with expelling Girard from the village. In Turn 1, the Prussians began with two special events, both to boost their artillery: one round of off-table grand battery fire and a card that allowed all on-table artillery to fire. Neither made much difference, to my deep annoyance. The Prussians advanced on both wings, towards St Amand La Haye in the East and through Wagnelée towards Le Hameau in the West. In front of Le Hameau, the French focussed artillery and skirmish fire on one Landwehr battalion, nearly bringing it to break point in one turn but fortunately, I had a rally card that included militia so avoided a rout, at the cost of a lost stand. In the East, the Prussian advance got off to a slow start but by turn 2 I was ready to charge St Amand La Haye. Or not. The 28th Line, ordered into the village, declined to advance so fired an ineffectual volley instead. I hate/love the Charge mechanic! In retrospect, that might have been the time to use a Command Point for a discipline test reroll. So turn 2 ended with no serious combat in the East and some enterprising French skirmishing and artillery bombardment in the West. At this point, we called time for food and drink. Phase 2 of the game saw a change to solo play as Keith was sent back to Devon. The two sides were now in striking range and each made aggressive moves on their left. In the West, helped by the arrival of their reserves, the French stopped the Prussian right dead and pushed it onto the defensive. In the East, the Prussians tried again to assaut St Amand La Haye and this time, at least they managed to charge home. However, the first combat went against them. The Prussians regrouped and the second assault pushed one French battalion out of the village. The French lacked reserves on the right so transferred two battalions from the left to try and retake the lost sector of St Amand la Haye, which they successfully did. All the while, victory points were accumulating as both sides had to shore up crumbling units. At the end of turn 4, French VPs exceeded the Prussian morale total so Girard won the day. I don’t play solo games that often but enjoyed playing this through to a conclusion. The Second GameIn the second game, Spencer took the French while Dan and I shared the Prussians (Dan on the left, me on the right). To cut a long story short, the Prussians attacked St Amand La Haye from two sides and after shooting up a seasoned French Line battalion, they got a battalion into St Amand La Haye and managed to hold on there. The French left came out swinging to try and disrupt the Prussians right, but rolled some very unlucky dice and stalled in the Standing crops. On the French right, a lone battalion charged and roughed up some Landwehr and French skirmishers caused a ot of disruption, but when it mattered, French dice rolls were particularly unlucky. Dan meanwhile ground steadily forward, his men watched by Blücher himself. French morale broke at the end of turn 4. At this point French reinforcements were just arriving on the table, too late, alas, to alter the outcome. Post-Match AnalysisThese were two very entertaining games. The rules flow easily and both battles ‘felt right’. We especially like the skirmishing rules, which, for me, are way better than the bucket of dice palaver used in Lasalle 2. The choices players face are constantly challenging: is this card more valuable for its order value, for its special event or for the troop qualities it can rally? It will take a few more games to be sure but my evolving feeling is that special events should be used sparingly, however much fun they seem. This is particularly true for the attacking side. By all means play a special bombardment event before charging in but every card played for its special event is one card fewer for moving units towards the enemy. Also, make sure you hang on to the rally card that covers the troop qualities in your army. The Prussians in this scenario have 4 Landwehr units who can quickly get into trouble if you don’t have a rally card that covers their militia quality.

In the Facebook Soldiers of… Group, somebody wondered if small units would survive for long on the table against much larger opponents. This scenario has a number of 3-stand French battalions and overall, the Prussian battalions are significantly larger than their French opponents. We certainly found that the smaller French units held their own well. Unit size is of course a factor, but so are troop quality, skirmish ability and formation. I was impressed in the second battle by how quickly the game played. We had all got our heads around the mechanics by then so we rattled through each turn. In truth, the movement, firing and melee mechanics are very straightforward and logical. The challenges in these rules derive from the card play, not from long lists of dice modifiers. This is as it should be. I have no niggles with these rules. There are however a couple of unit stats in the rulebook that I am not sure about. For example, in the Army lists Prussian Foot artillery is only allowed to be 12 pounders, whereas in reality the majority of Prussian field foot batteries were 6 pounders. This might even be a typo I guess, and it’s no hardship to ignore the lists and give the Prussian foot batteries 6 pounders. I am also tempted to revisit the stats for Prussian Landwehr, some of whom were, by 1815, veteran units with fearsome reputations. We needn’t go overboard here but it may be fitting to increase the quality of Landwehr from the older Prussian provinces (and hence recruited first) from Militia to Trained. This small shift would make quite a difference to the staying power of a Silesian Landwehr battalion. Finally, the scenario worked well, though I tweaked the objectives for Prussia between games 1 and 2 to make St Amand la Haye more important (they were given the Take a Strongpoint objective, but only redeemable in that village). Overall, I am delighted with these rules and I look forward to the first supplement. I have uploaded a new scenario here for Soldiers of Napoleon (Scenario SoN 3), covering Girard’s 7th Division’s defence of St Amand La Haye during the Battle of Ligny on 16 June 1815. I started with the Lasalle scenario that I had already written for the same action, but was soon moved to revisit the sources because of an interesting difference in approach between the two rule sets.

Lasalle 2 makes all units a standard size (Russian artillery excepted). Lasalle 1 did have an option for large battalions, but even then there were only two sizes. Sam Mustafa is an accomplished designer who tests his rules extensively before releasing them. Lasalle 2 works very well indeed and there is no doubt that standard unit sizes (and hence frontages) makes for smooth play. The argument for standard sizes generally runs that it is hard to know exactly how many men were present at any given point and that on average, most battalions were around 500 men strong after a few months campaigning. If an army’s battalions were seriously understrength, as the Russians often were in 1813, the player is free to represent two actual battalions with one model battalion. Fair enough. I didn’t give much thought to this approach until reading through Soldiers of Napoleon. The approach to unit creation in Soldiers of Napoleon is more fluid than in Lasalle 1 or 2. A battalion can be any starting size from 2 to 6 ‘stands’ and the rules for firing, melee and morale management are geared for this. Looking at the orders of battle n the 1815 campaign, I was struck by the wide variation of battalion strengths between the French and Prussian armies. On the whole, Prussian battalions are significantly larger than the French. Now, at the scale of a divisional fight, the difference in battalion sizes could have a significant impact on play. So in adapting the Girard scenario to SoN, I have tried to reflect actual unit sizes in the order of battle (using the ratio of 132 infantry or 100 cavalry to a stand). Consequently, the largest unit is a Prussian Line battalion of 6 stands and the smallest is a 3-stand French battalion. I look forward to testing the effect this has on scenario balance when we play it on 11 September. I have a feeling that Girard is going to have a tough time hanging on to his real estate! SummarySoldiers of Napoleon provides a fast-moving and entertaining game. The cards pose tricky choices and have bags of period flavour. Our historical scenario gave moments of high excitement and a plausible outcome. Highly Recommended. DetailI recently bought Soldiers of Napoleon, the new card-moderated tactical rules by Warwick Kinrade, author of Battlegroup (and more besides). Five of us played our first game last week, using a scenario based on the fight for Markkleeberg during the Battle of Leipzig. This clash between Poles, French, Prussians and Russians seemed a good testing ground for the rules. The mechanics for movement, fire and melee are intuitive, straightforward and easy to learn. They hang together well, give good period flavour and on their own could have been the basis for a respectable IGO-YOUGO game. The card deck, however, takes things to another level. Every turn, each side receives a hand of cards linked to the number of Brigade or higher commanders on the table and players alternate card play until both run out. A card has three possible uses: to issue orders to a given number of units within a brigade; to rally units; or to play the special event that is described on the card. I’ve seen a couple of reviews that describe the rules at length so rather than repeat it all again, I’ll try to show how they affected our battle. I have put the Markkleeberg scenario here. I created it by following the game preparation procedure in the rules. The main Tactical Orders for both sides were chosen for them (Coalition attacking, Franco-Poles defending). The Order of Battle was fun to write because SoN doesn’t have standard unit sizes. A battalion or cavalry regiment can have between 2 and 6 stands, or roughly between 250 and 800 men. This suits the OoB for Markkleeberg well, as Helfreich’s 14th Corps was seriously understrength (so 3 stands per battalion), the Polish Cuirassiers only consisted of 2 squadrons/bases and the Prussian Landwehr battalions were numerous (but inexperienced). How the game playedWe played the scenario with two players per side. The Poles deployed their three brigades first, then the Allies set up in left echelon. Both sides had reserves off the table. The Russian 14th Corps advanced on the right; Coalition artillery in the centre bombarded the Polish hilltop position and the Prussian Foot screened Markkleeberg on the left. The Poles played a special event early on that allowed the Krakus lancers to advance far down the table and catch and destroy a Russian battalion in column (an incident that was only made possible by the special event: without it, the Russians would have had time to form square and fire at the threatening cavalry). This dislocated the Russian assault and bought time for the defenders, while the rest of Helfreich’s Corps formed square until the Krakusi retired. The Poles used another special event to bring in fire from the Grand Battery to their left rear. Phase 1 therefore gave the advantage to the defenders. In phase 2 the Russian assault got going again. A counter battery exchange in the centre went badly for the Poles and the Coalition artillery then whittled down the Vistula Regiment in the Polish centre as 14th Corps closed, supported by the Loubny Hussars. The French Reserve brigade arrived on the right and this, together with the Polish garrison of Markkleeberg, went forward to relieve pressure on the centre. Two Polish battalions chewed up a Prussian Landwehr battalion near the village and the Coalition left was now looking shaky. In response the Coalition played a special event to change the arrival location of their reserves to the Markkleeberg sector, which helped stabilise their left. In the final phase, the Coalition managed to shoot the Polish Division commander by playing a special event. The Russians then closed with the Polish centre and duffed it up enough to win the victory. The Love Child of Battlegroup and Longstreet?I love these rules! They do remind me of Longstreet, my (so far?) favourite rules for any period, which are also card-moderated and have a similar mixture of simple mechanisms and really challenging choices. Like Longstreet, SoN makes events possible that just don’t happen in many wargames, such as surprise attacks, missing ADCs, incoming damage from off-table batteries and stray bullets taking down senior officers. The sense of narrative and of history is really strong, which shouldn’t be a surprise from the author of Battlegroup.

All involved in this game want to play again and we all took away some thoughts on how better to play the cards next time. |

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed