Two refights and a post-mortemI have recently hosted two games set in Eastern Europe, using For King and Parliament (FKaP) by Simon Miller and Anthony Brentnall. In both games we fought the historical scenario for the Battle of Lubar, which is on the 17th Century scenarios page here. Background to the battle of LubarThe battle of Lubar (or Lyubar) was fought between a Muscovite-Cossack army and a Polish-Tatar force. It was the first engagement in the 1660 Ukrainian campaign, which took place during the Thirteen Years War between Muscovy and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Lubar was actually an engagement over many days, most of which consisted of minor actions during an extended blockade. The action on 16 September 1660 was the only occasion when the full complement of both armies went toe to toe. We have played games based on Lubar several times in the past few years, first using Warlord Games’ Pike and Shotte, once with Maurice, then with Tercios by el Kraken and now using FKaP. All of them were interesting games but for my taste, FKaP gave the most satisfying game. Each of the rules we have used so far required a little tweaking to cover the troop types present at Lubar. The one set that we could have played without any amendment is ‘With Fire and Sword/Ogniem i Mieczem’ by Polish company, Wargamer. These rules and the fantastic figures and terrain released for them have opened up this period to non-Polish gamers and I have hundreds of their figures in my collection. The only thing is, I cannot get on with the rules themselves. As the saying goes, I am sure it’s not Them, it’s Me. A couple of weeks ago, Wargamer announced that they are to replace With Fire and Sword with a quite different version. I will pick these up and perhaps WFaS Reloaded will hit the spot. Adapting FKaP to Eastern Europe17th century warfare in Eastern Europe had more in common with the West European experience than some might presume, especially as the century progressed. So the bones of FKaP work very well as they stand. There were however some troop types, weapons and tactics that were unknown in the West and I wrote a small set of rule adaptations to cover them. Most of these were rules brought forward from Simon Miller’s Ancients rules, To the Strongest, so fitted in comfortably. I’ve adjusted them a few times after playtesting and the current version is on the scenarios page here. Lubar refight: Take 1Earlier this month I hosted the first refight, with Chris playing Muscovy and Paul leading the Poles and Tatars. Chris deployed his Cossacks in his main camp with a regiment in the forward trench on his right. He put Muscovite infantry with light guns in the redoubt on the left, with some cavalry behind them. The rest of the cavalry joined the infantry in his main camp. Paul placed his foot and artillery in his centre, with his cavalry divided between Potocki on the right and Lubomirski on the left. Paul left space on the left for his Tatar Allies to arrive (-and leave: the scenario makes their presence unreliable at best). The battle began with a spirited assault by the Tatars on the Cossack trenches, while the Polish infantry advanced on the hilltop redoubt. Chris responded to the hilltop assault by sending cavalry around the eastern side of the hill to threaten the Polish flank. Paul challenged this assault with pancerni and a unit of hussars, which blotted its copybook early on by failing to activate to charge, drawing the dreaded two 1s in succession. Paul was admirably calm about this and the hussars redeemed themselves on their next activation, smacking up some Muscovite Reiters and blocking Chris’ outflanking attempt. On the left the Tatar command steadily drained away, as units left the field in search of easier plunder, but not before they had caused impressive damage to the Cossacks in the trenches. Paul even managed to break into the main enemy camp, if only temporarily. The game ended with Chris handing over his last victory medal but he was still well established in his main camp and as Paul’s medals were also running low, we agreed this was more a winning draw than a walkover. In our after-action discussion, we agreed the game’s outcome was remarkably similar to the history: the Poles and Tatars had the advantage in the open with their superior cavalry, while the Muscovite and Cossack infantry were a tough challenge for the outnumbered Polish foot to beat. Both players attacked the scenario with gusto and picked up the rules easily. Refight Take 2After the first game I adjusted two aspects of the scenario. First, I moved the Muscovite camp one square westwards to make the land around the Muscovite hill more open to a flanking manoeuvre. I also changed the scenario special rules for the Tatar forces to make them last a little longer on the table. Game 2 saw Rupert’s Muscovites and Cossacks facing Kevin’s Poles and Tatars. Both sides deployed rather differently from the players in game 1. Rupert put his infantry in the hilltop redoubt, the trenches in the forest and his main camp, then deployed his cavalry in a line in front of the camp. He placed his field artillery in the trenches, initially facing forward but later rotating to enfilade the advancing Poles. Kevin drew up with his cavalry commands on the left and centre and his infantry on the right, facing the hilltop redoubt. On his first turn Kevin started an outflanking attempt with two infantry units and some dragoons, aiming to get around the eastern end of the Muscovite redoubt. Unfortunately, this manoeuvre was plagued by poor activation attempts throughout the day and by game’s end was still slogging up the table, without ever coming to grips. At the same time the Polish foot in front of the hilltop redoubt spent the day waiting for the outflanking force to get into position and so the entire Polish infantry complement was basically uncommitted throughout the game. The Polish cavalry and the Tatars, by contrast, were heavily engaged from the start. The Muscovite cavalry launched a spoiling attack as the enemy advanced, which considerably disrupted the Polish front line. However this attack then exposed the Muscovite horse, now variously out of pistols or spears and low on dash, to the still-fresh Polish second and third lines. The result was to be expected and in one turn, several Muscovite victory medals were handed over to the enemy. But with the Muscovite and Cossack infantry in the main camp now able to fire on the enemy cavalry, the balance of damage was nearly restored. It was clear that the Polish cavalry would not make headway against the entrenched Muscovite and Cossack foot and, with real time running low, we agreed that the Poles would not press home their attack and the battle ended. This was an interesting game, in which the deployment of both sides was unexpected. The Poles, already outnumbered in infantry, effectively left their Foot out of the battle by stacking them on their right and attempting the outflanking manoeuvre. Even if they had had more success with activation draws, the Polish ‘right hook’ would still have spent a lot of time getting into position before engaging. Kevin commented that if he had assigned the task to cavalry, the result could have been very different. On the other side, the screen of Muscovite cavalry across the centre delayed the Polish advance, but it was both outnumbered and outclassed by the cavalry facing it and it blocked the fire of its own infantry behind it. Once that infantry was given a free field of fire the prospects for the Polish horse became less rosy. Perhaps the Muscovite Horse could have withdrawn sooner once it inflicted the first reverse? All of this is easy for me to say, but I wasn’t playing the game. Both players showed considerable aggression and the cavalry confrontation in the centre was particularly hard-fought. Kevin certainly made the most of his flakey Tatar units, which did stay on table for longer than in the first game but were still sloping off the field at inconvenient moments. The game versus history: how credible were the results?I was frankly delighted by the way FKaP played out in both games. On a general level, the results were reassuringly similar to what happened in history, especially in the first game. The way cavalry performs is particularly satisfying. The clash between the Muscovite and Polish horse in the second game felt just right: the Muscovites were slightly, but not hopelessly outclassed in the initial combats but the Poles had the advantage of fresh units ready to challenge the increasingly tired Russians. As the saying goes, numbers have a quality all of their own.. The Tatars also behaved as I would expect. They are primarily a nuisance and with only one hit are brittle, but they can be devastating against an enemy that is already disordered and tired. Also, their sheer numbers can help them to overwhelm a superior opponent. The evade rule, adapted from To the Strongest, works fine. As for the infantry, pike and shot are suitably ponderous while the smaller Haiduk and Streltsi units are a little easier to move. Finally, artillery can occasionally do damage but isn’t a battle winner, which is appropriate for this period. In short, I think after these games that the Eastern Europe adaptations for FKaP are about right. Earthworks were an important feature of the battle of Lubar and I was impressed by the way they work in FKaP. Based on accounts of battles in this period, they should give an advantage to troops defending them but ought not to be impregnable: during the battle of Lubar, attackers did break in, both to the hilltop position and the main Cossack/Muscovite camp. I am increasingly impressed by FKaP: these rules are easy to learn and deceptively straightforward. New players pick up the mechanics very quickly but they face multiple choices and challenges each turn. The next battle I’d like to try is Polonka (great name!), the battle between Muscovites and Lithuanians fought earlier in the same year of 1660. This was an encounter battle without prepared positions and I’ll be interested to see how it plays with these rules. Figures and game aidsThe figures in our games were 15mm by Wargamer, Essex Miniatures, Lancashire Games (both from today and the 1980s) and a superb Spanish producer who had a stand at Salute some years ago, but whose figures I haven’t seen again. The game mat is by Deep Cut Studios, bought from Simon Miller’s Big Red Bat Shop. We used Simon’s ‘chits of war’ for activations, also available from his shop, and used ten-sided dice to resolve combats.

6 Comments

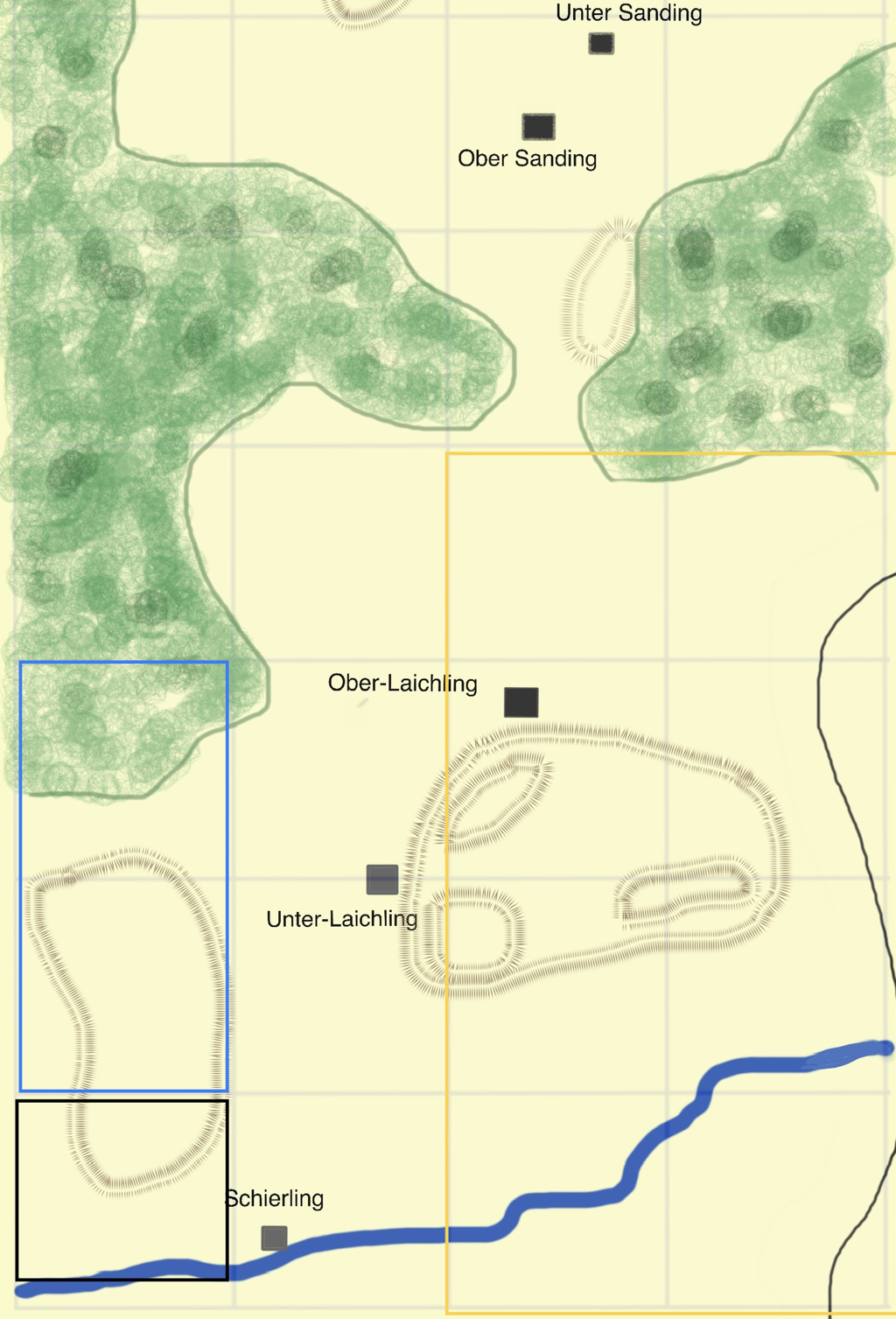

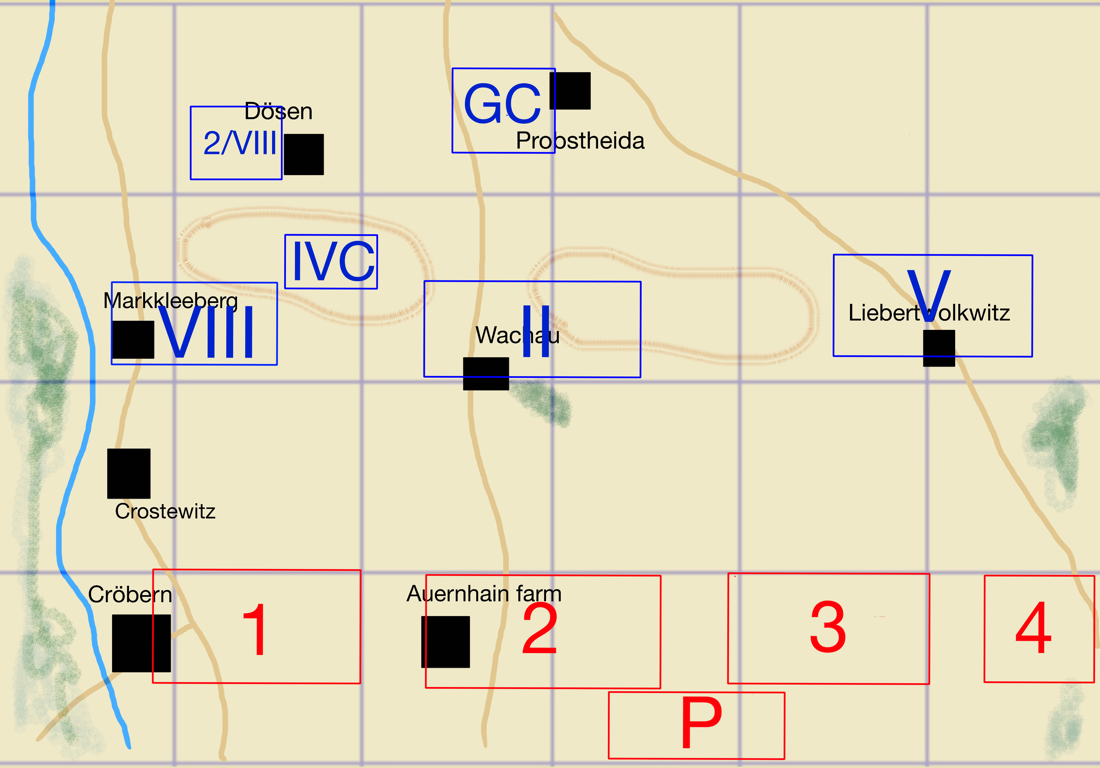

It is some time since I last played a 17th Century game but earlier this year I was tempted back after reading Michał Paradowski’s new book published by Helion, “Despite destruction, misery and privations” about the Polish army fighting the Swedes in Prussia in the 1620s. This fascinating book is full of detailed information about the recruitment, equipment and organisation of the Polish forces. I rather wish it had also described the course of the war, if only in general terms, for the benefit of non-Poles like me who don’t already know the history. But I still strongly recommend it to anybody with an interest in the period. Over the years our gaming group has tried a few rules sets for 17th Century Battles in Eastern Europe. My favourite for some time have been Tercios by el Kraken, but the need to issue a separate order card to every unit can make bigger battles a bit slow to play. When Simon Miller and Andrew Brentnall released ‘For King and Parliament’ three or so years ago, I picked them up because I really like Simon’s Ancients rules, ‘To the Strongest’. FK&P doesn’t have rules for several east European troop types but they are easily adaptable. With a bit of borrowing from To the Strongest, I drew up some house rules to adapt FK&P to battles further east. We played a test game based on Berestechko, 1651, which went well. I then started on troop stats for 1660, which added Muscovite troop types to the mix. At that point I was distracted by a rebasing project for my 15mm Napoleonics and 1660 went onto the back burner. Thanks to Paradowski, I have now hauled it out again and done some more work on the house rules and troop stats, and have written a couple of scenarios to test them. The latest house rules are here Two scenarios for the price of oneThe scenarios are set during the 1660 Chudnov/Cudnów campaign, between the Commonwealth and Tatars on one side and a Muscovite-Cossack alliance on the other. I love taking ideas from this campaign! It offers several candidates for an interesting game, including a clash of advance guards, a running fight, a rearguard action at a ford, a field battle and an assault on the enemy camp. Both of the new scenarios are based on the third day of the battle of Lubar on 16 September 1660. The historical version represents an attack by the Poles and Tatars on the enemy camp. The second is a What If scenario, involving a battle in the open ground between the two camps. This scenario presumes the Poles adopted a battle plan supposedly put forward by Field Hetman Lubomirski. Both scenarios can be found here. We played the What If version as a multiplayer scenario in 2014 using Warlord Games’ Pike and Shotte and It gave a balanced game. I later converted the orders of battle for the Tercios rules and we played the historical battle in 2016. Last week I played the historical FKaP scenario with Chris and Paul and will play it again this Friday with two more opponents, Kevin and Rupert. I will post battle reports and photos after the second game. Meanwhile, as English language accounts are hard to come by, I have written an account of the battle below. It is based on a few sources, mainly Łukasz Ossolinski and Mirosław Nagielski. The battle of Lubar 16 September 1660

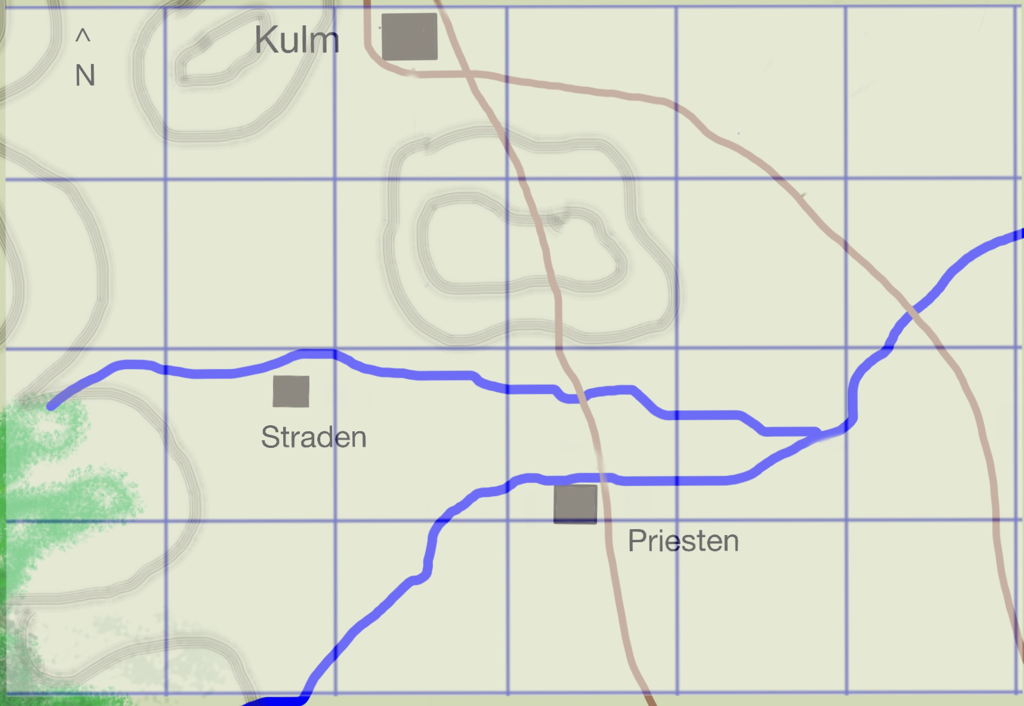

The battle of Lubar was the first act of the Chudnov campaign of 1660, when a Muscovite-Cossack alliance took the field against the armies of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and their Tatar allies in Ukraine. Lubar was in fact a confrontation over several days. It began on 14 September with a chance encounter between the vanguards of the Commonwealth-Tatar army and the main Muscovite-Cossack army led by Sheremetyev and Tsetsura. Having made contact, the two sides made camp within a few kilometres of each other. At this time it was standard practice to fortify in the presence of the enemy, first by placing wagons around the perimeter and if a long stay seemed likely, by digging earthworks. After the initial clashes of the 14th, both sides spent the 15th strengthening their camps and preparing for battle. The Commonwealth and Tatar camps were placed near the town of Lubar, with easy access to fresh water and forage. Sheremetyev and Tsetsura’s camp was well situated for defence with forest to its rear and an emplacement on high ground covering its southern side, facing the enemy. However, it was poorly suited to a long stay, as forage was scarce and its water supply was a marshy stream that was barely able to meet the needs of 30,000 men and their livestock. On 16 September, the opposing forces drew up in battle array, facing each other between their camps. The Commonwealth army had an interest in fighting in the open, where it could take full advantage of its superiority in cavalry. The enemy was believed to be unaware that Field Hetman Lubomirski and his division had arrived in theatre to join Grand Hetman Potocki. According to some accounts, Lubomirski proposed setting a trap, by hiding his troops behind high ground and drawing the enemy further into the open before launching an ambush. For whatever reason, no trap was laid and the whole Commonwealth army advanced on the enemy. In response, Sheremetyev withdrew the bulk of his army back behind his camp earthworks, leaving two forward garrisons: the fortified hill in front of his left, occupied by infantry and artillery with cavalry hidden behind the hill; and trenches in front of his right, occupied by Tsetsura’s Cossacks with light artillery. The action began with an assault by Potocki’s Command on the Muscovite-held hill. The first attack, by Polish dragoons, overran the position and forced the enemy infantry out. The Muscovites counterattacked and retook the hilltop, to be ejected in turn by some of Potocki’s ‘foreign’ foot. Meanwhile a cavalry fight developed around the base of the hill, with both sides feeding in reinforcements. The hilltop may have exchanged hands again in the course of the fight but by late afternoon it was in Polish hands and the Muscovite forces had withdrawn to their main camp. With the hill in his possession, Potocki ordered his troops to prepare to assault the main enemy camp. However, as his infantry formed up in front of the Muscovite earthworks it was disrupted by heavy artillery bombardment and this evidence of Muscovite determination, combined with the advanced hour, prompted Potocki to call off the assault. On the Commonwealth left flank, Lubomirski’s infantry attacked the Cossack forward trenches and eventually cleared them. Again, given the late hour, Lubomirski did not wish his troops to go on to attack the main camp, from which the Cossacks kept up a determined fire. At this point, according to Polish eyewitnesses, an incident occurred that led to the fight restarting. Throughout the day, the Tatar contingent had been coming and going from the field, harassing the enemy with bow fire and looking for weaknesses around the enemy position. Shortly after the Cossack trenches had been cleared, a senior Tatar warrior fell wounded from his horse in front of the enemy camp and a group of Cossacks jumped out from behind their earthworks to take him prisoner. Seeing this, those Tatars in the vicinity rounded on the Cossack group, saved their wounded comrade and amidst the confusion, pursued the enemy back inside the camp. More Tatars followed and were joined by Polish horse and a regiment of foreign foot, all of whom broke into the Cossack earthworks. The infantry commander believed the Cossacks were breaking and urged that the breach be exploited, but Lubomirski insisted that all troops return to Polish lines. The day therefore ended with the Commonwealth army abandoning its gains on both the left and right wings and retiring to its own camp. The fighting on 16 September illustrated the strengths and weaknesses of the opposing armies. Sheremetyev and Tsetsura were outclassed in the cavalry arm so unlikely to win a battle in the open. Potocki and Lubomirski meanwhile had too few infantry to carry the enemy camp by storm. Sheremetyev decided to stay behind his earthworks and wait to be reinforced by Chmielnicki’s 20000-strong Cossack army, which was only a few days’ march away. Potocki and Lubomirski laid siege to Sheremetyev’s camp. Over the days that followed, the Muscovite/Cossack camp, hemmed in by the Commonwealth/Tatar blockade, began to suffer from the poor water supply and limited access to fodder. Moreover, Chmielnicki showed no signs of advancing to reinforce Sheremetyev, despite exhortations to hurry up. On 26 September Sheremetyev retreated to his forward supply depot at Chudnov, pursued a little belatedly by the Commonwealth army. The next day, the two armies settled down again in much the same situation as before, with Sheremetyev blockaded in his camp by the Poles and Tatars. There would follow several minor engagements, a battle at Słobodiście and the desertion of his Cossack allies before Sheremetyev was forced to surrender and marched his army into captivity. As events turned out, the confrontation at Lubar on 16 September had been the high point of Muscovite fortunes. Late in 2018 I posted some house rules for adapting For King and Parliament to campaigns in Eastern Europe. These included unit statistics for Cossack and Commonwealth armies, around the time of the Berestechko campaign of 1651. Recently I extended the stats to cover Muscovy. I have been rereading an account of the 1660 Cudnów/Chudnov campaign, in which a Muscovite army advancing in Ukraine was checked and later defeated by the joint Polish forces of Lubomirski and Potocki. 1660 offers lots of scope for scenarios, including a meeting engagement, a set piece battle with a surprise twist, a rearguard action and an assault on a fortified camp. I have three different accounts of the campaign including detailed orders of battle and it cries out for some wargames.

. Back in 2015 and 2016 we fought several games based on 1660, first using Pike and Shotte and later using the Spanish set, Tercios/Kingdoms. Both rules gave satisfying games and I particularly like the mechanisms in Tercios, but I’d love to see how the bigger actions in particular play using FKaP. The first scenario I plan to run is the battle of Lubar, in which the Muscovite general, Sheremetyev, offered battle in the belief that he outnumbered the enemy. It was his first and only foray into an open field. I have uploaded the new unit stats and FKaP army lists for Cudnów here, I am still working on the map and scenario for Lubar and will put this up when it is a bit more polished. I have had another go at the house rules for adapting FK&P to Eastern Europe. For now we are just looking at the troops needed to refight the battle of Berestechko in 1651, so involving the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth, Zaporozhian Cossacks and Tatars. When we are happy with these I’ll have a look at Muscovy. The current house rules are here . This is a lot of fun to do. Poor Matt is going to find himself in the gaming equivalent of Groundhog Day before we are satisfied.

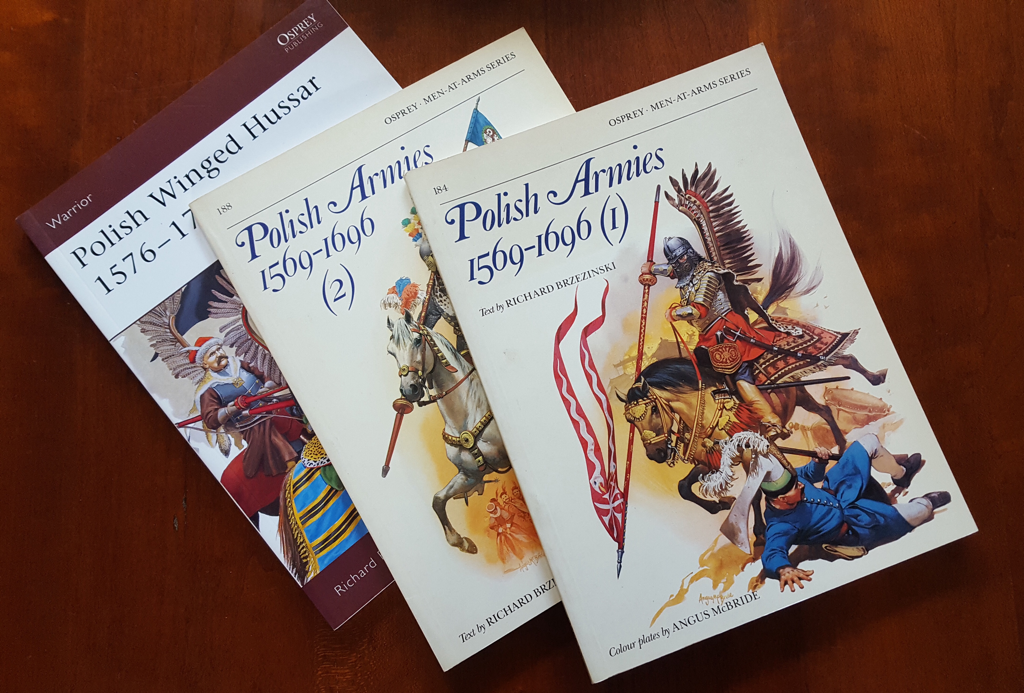

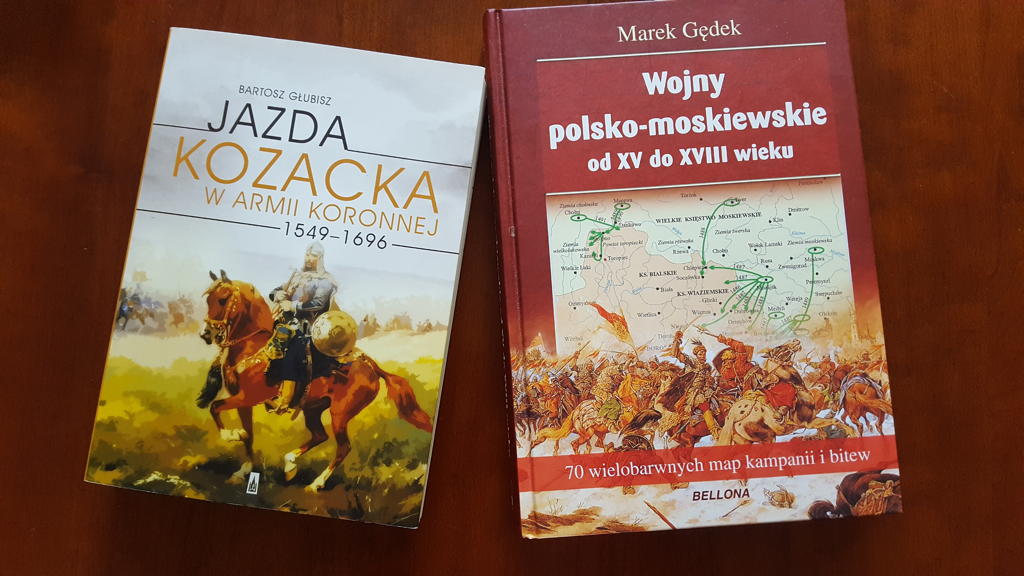

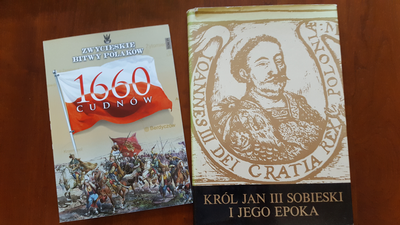

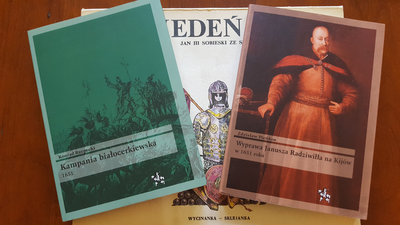

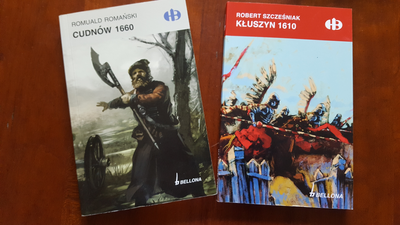

In a recent blog comment, Neil Burton asked if I could provide some sources for warfare in 17th Century Eastern Europe. I’m afraid most of my detailed sources are in Polish but there are some useful Ospreys and a growing collection of material in English on the Intranet. Polish Armies 1569-1696, by Richard Brzezinski, is published in two volumes by Osprey (numbers 184 and 188 in the Men-at-Arms series). Volume one concerns the ‘national’ Polish formations and volume two is about the ‘foreign’ section. The illustrations by Angus McBride are particularly good. These books only suffer from the limitations of the format: while a great introduction, they barely scratch the surface of the wars of this period. Richard Brzezinski wrote another useful book for Osprey in the Warrior series, published in 2006, called Polish Winged Hussar 1576-1775. Another really helpful source of information are the rules With Fire and Sword, by the Polish company The Wargamer. They provide lots of information about the different troop types as well as campaign backgrounds and tailored orders of battle. I am not attracted to the rules themselves but they are still worth getting for the background material and illustrations. On the Internet, there is a lot of English language material on Wikipedia. The following links are good starting points and each will take you to several other useful pages, especially about battles. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deluge https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khmelnytsky_Uprising https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Northern_War https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russo-Polish_War_(1654-1667) The following site is dedicated to Polish renaissance warfare. http://www.jasinski.co.uk/wojna/index.htm The last site to recommend is the home page of a re-enactment society, which contains a varied mix of useful articles, from dress and equipment to discussions about tactics. I have spent a lot of time on this site and really enjoy searching it. http://www.kismeta.com/diGrasse/PolishHorseArtillery.htm In case you speak Polish, these are books I have picked up for myself in recent years. New titles appear regularly and it is worth entering the name of a battle on Amazon to see what comes up. I found the two books about Cudnów (1660) that way. i wish this period and theatre was easier to access, since I find it so fascinating. But by looking here and there across the Internet, you will find a great deal of interest.

On 15 September, Keith, Matt and I spent more money than was good for us at Colours in Newbury. I like this venue, especially the light upstairs floors that are a much more pleasant environment than some Show venues. On the second floor, messrs Miller and Brentnall were demonstrating a beautiful 28mm game of For King and Parliament. Having left the dog home alone, I prevailed upon Keith and Matt to leave Colours at lunchtime and come back to play a game. We agreed to try the new stats I have been brewing for using For King and Parliament in Eastern Europe. I set out the table using the battlefield of Berestechko, but as it was our first play test the army sizes were considerablyreduced. Matt, as King Jan Kazimierz, had two sub generals: Jeremi Wiśniowiecki, commander of the left; and Stanisław Lanckoroński, commander of the right. His army contained: 1 unit of Hussars 5 units of Pancerni 1 unit of Reiters 1 unit of Dragoons 1 unit of Hajduk infantry 2 units of German infantry 2 units of field artillery. Keith, as Bohdan Khmelnytsky, also had two generals: Ivan Bohun, commander of the Cossack right and Islam Giray, Tatar commander on the left. His OOB was: 3 units of registered Cossacks 2 units of Zaporozhian Cossacks 1 unit of Cossack horse A fortified camp, 3 squares wide and 2 deep, with its front on the 3rd row of squares 2 light Artillery pieces for attachment to Cossack units 1 unit of noble Tatar lancers 3 units of Tatar lancers 3 units of Tatar light cavalry bowmen In line with historical deployment, Keith set up his cossack foot on his right, inside the Tabor, with their horse outside and immediately to its left. He set up his Tatars on the left, with the bowmen on the far flank and lancers closest to the centre. Matt deployed a small command of two Pancerni and the Dragoons on his left; his infantry, artillery and Reiters in the centre and the rest of his Horse on the right. As this was a play test, the point was not to try and win but to test different aspects of the rules. Both players took a few decisions to see what would happen, possibly against their better judgement. Keith in particular wanted to gauge the flexibility of his Tatar troops and they saw the most action of the game.

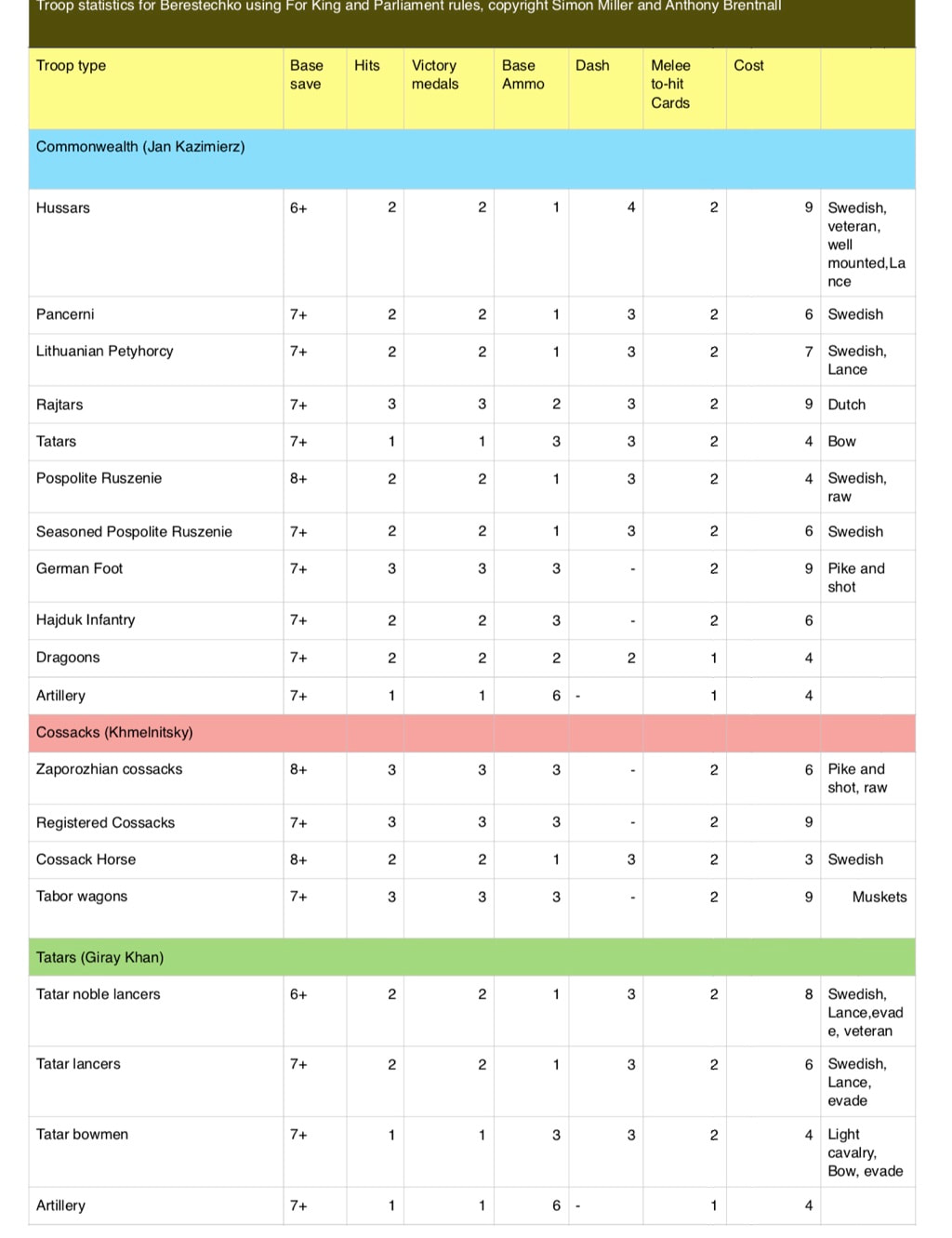

The battle began with Matt advancing his right and centre, while his left observed the Tabor from a safe distance. Keith kept his Cossacks tucked up in the Tabor and advanced his Tatars, with his bowmen looping around on the far left. The bowmen were charged by Pancerni but evaded, falling back on the woods to their rear. Keith then decided to see what happened when lancers charged the front of a Pike and shot batallia. Reassuringly, they slid off. Never one to learn from a mistake, he repeated the experiment with another lancer unit, with the same result. The second melee was closer run however, as the Foot had picked up a disorder in the first combat, but the odds were still in their favour. In another combat, Matt’s Pancerni destroyed a Tatar lancer unit in one round. At this point I realised I hadn’t thought about the applicability of the FKaP pursuit rules to Eastern Europe. Uncontrolled pursuit by mounted units was not a significant feature of the dozen or so battles I have read about, although I’m sure it must have happened. We need to think about this but I am tempted to tone down the pursuit rules for games in the East in some way. The battle ended with the collapse of Keith’s Tatar force and death of Islam Giray. As I say, however, this wasn’t really a competitive game but a first chance to try our adaptation. So everybody was a winner, or at least, everybody certainly enjoyed the game. How did the rule adaptations work? First, as we expected, the basic mechanisms of FKaP worked very well for activating and manoeuvring the armies. The Pancerni and Tatar lancers performed as we thought they ought. I was particularly pleased with the way the light cavalry bowmen worked: they were a flexible irritant that kept dancing out of danger but collapsed when cornered. This game didn’t give us a chance to test the resilience of the Tabor as Matt didn’t assault it. In the real battle Wiśniowiecki charged it with his cavalry and was repulsed. We will have to set up a few assaults to see how it fares. Of course we’ll need to play several more test games to get a reliable feel for the whole set of changes. But after one outing, I am very encouraged, especially by the way light cavalry work. One more thing. For King and Parliament is a cracking set of rules: fast, tense and great fun. The next few months are going to be fun. I have set out to adapt Andrew Brentnall and Simon Miller’s ECW rules, ‘For King and Parliament ‘, to cover Eastern Europe and specifically, the Battle of Berestechko, 30 June 1651. Although some east European troop types are not covered by these rules, most of them are either directly covered or can be represented by equivalent unit stats. The myth seems to linger (in Western Europe that is) that warfare in the East was more ‘primitive’ than in the West, with armies full of lassoo-wielding savages on steppe ponies. It’s true that some specific troop types existed and that in general, the cavalry arm was a bigger proportion of eastern armies than in the West. But most of the troop types present in the Commonwealth armies of the 1650s would be recognisable in a west European force (indeed, many of the troops were recruited from Western Europe) and in wargaming terms, the mechanics and many unit stats in For King and Parliament are applicable with little or no adjustment. The following are my first thoughts about adapting the rules to the East. I will revisit them after a few games. Commonwealth troops Hussars count as well-mounted, veteran Swedish-style Horse, armed with a lance (conferring a one-off extra to-hit card). This is fitting, given that Gustavus Adolphus had based his new cavalry tactics on those of his fast-charging Polish opponents. Pancerni count as seasoned Swedish-style horse. Petyhorcy count the same, with an added lance. Reiters could be Dutch, or increasingly Swedish as the century progressed. As accounts of Berestechko describe the Reiters as providing fire support in the Centre rather than in the cavalry wings, I am inclined to make them still Dutch in 1651. ‘German’ foot are standard pike and shot units at a 1:2 ratio. Haiduk infantry have the same stats as commanded shot. These troops operated in smaller units than German foot so the original stats can stand. Most were seasoned troops. Dragoons also read across directly, although the Commonwealth used them in great numbers and they were among the most hard-worked troops in the borderlands given their ability to keep up with the cavalry. Some dragoon units had pikemen as well as shot and they could hold their own in the main battle line. There may be an argument to treat some Dragoons as veterans and/or to give them pikes but I amleaving them as standard for now. Artillery also reads across without change. Pospolite Ruszenie are the Polish ‘noble’ levy, summoned by the King in hour of need. These troops were famously unmanageable and of mixed quality. The practice of calling the noble levy would die out over the rest of the century. I have shown them as Swedish style but raw, although they could also be untried. A small number of units, mainly from South and Eastern Poland, were battle experienced and fought well, so these will be seasoned. Cossack forces ‘Registered’ Cossack units represent experienced troops who left Commonwealth service to join the rebellion. They were regarded as some of the best infantry in Europe by contemporaries. I have made them the same size as German Foot but they lack pikes. The Zaporozhian Cossacks are less experienced than Registered Cossacks and so raw, although they do have short pikes. Cossack horse are equivalent to raw Swedish horse. The Zaporozhians were overwhelmingly an infantry army and their cavalry was indifferent. The Tabor is making me think. Cossack armies used their wagons to form temporary fortresses and the Tabor was a key part of their position at Berestechko. We are not talking about a fortified camp behind the lines, but a serious and deep defensive line protecting the front of the army. There were some engagements where the Tabor was attacked on the move. In such a case I would place wagon units on the table with their own factors. I have looked at the rules in To the Strongest for War wagons and have created Cossack unit stats based on them. But the approach I plan for Berestechko is to use the fortifications rule from FKaP. I’ll still place wagon models on the table but this time they won’t have intrinsic fighting powers, as these will go to the infantry units behind them. I will also give Cossack units a cover advantage in all squares enclosed by the Tabor as they drew up further lines of wagons behind the first. I will also hinder movement within this area. The Tatar Horde The Tatars have three troop types: noble lancers; standard lancers and bowmen. I have snaffled some rules from To the Strongest to cover Tatar troop types and tactics. Light cavalry: All light cavalry activations are considered easy. Light bow armed cavalry may fire and retire one box facing the enemy (as well as the existing movement possibilities in FKaP). Infantry can charge light cavalry (this represents the light cavalry falling back before a steady advance of formed foot. Foot may not charge any other types of horse). Light cavalry receive a +1 save modifier against shooting, to reflect their dispersed formation. Light cavalry and Tatar lancers have the evade ability. Cavalry with the evade ability may evade charging infantry on a 3+ and cavalry on a 5+. If successful they retreat one box facing the charger. (The Tatars were highly versatile horsemen who used the feigned retreat to lure enemy troops out of formation. I decided to give lancers the evade ability despite them not being light cavalry). These stats are set out in the table below. The points values may be a bit off here and there but I hope they broadly fit. On 15 September, fresh from a trip to Colours at Newbury race course, where we had seen a great game of For King and Parliament in full swing, Keith, Matt and I had a first play test of FKaP in the East. Stay tuned for the after action report in the next blog post

|

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed