|

It is some time since I last played a 17th Century game but earlier this year I was tempted back after reading Michał Paradowski’s new book published by Helion, “Despite destruction, misery and privations” about the Polish army fighting the Swedes in Prussia in the 1620s. This fascinating book is full of detailed information about the recruitment, equipment and organisation of the Polish forces. I rather wish it had also described the course of the war, if only in general terms, for the benefit of non-Poles like me who don’t already know the history. But I still strongly recommend it to anybody with an interest in the period. Over the years our gaming group has tried a few rules sets for 17th Century Battles in Eastern Europe. My favourite for some time have been Tercios by el Kraken, but the need to issue a separate order card to every unit can make bigger battles a bit slow to play. When Simon Miller and Andrew Brentnall released ‘For King and Parliament’ three or so years ago, I picked them up because I really like Simon’s Ancients rules, ‘To the Strongest’. FK&P doesn’t have rules for several east European troop types but they are easily adaptable. With a bit of borrowing from To the Strongest, I drew up some house rules to adapt FK&P to battles further east. We played a test game based on Berestechko, 1651, which went well. I then started on troop stats for 1660, which added Muscovite troop types to the mix. At that point I was distracted by a rebasing project for my 15mm Napoleonics and 1660 went onto the back burner. Thanks to Paradowski, I have now hauled it out again and done some more work on the house rules and troop stats, and have written a couple of scenarios to test them. The latest house rules are here Two scenarios for the price of oneThe scenarios are set during the 1660 Chudnov/Cudnów campaign, between the Commonwealth and Tatars on one side and a Muscovite-Cossack alliance on the other. I love taking ideas from this campaign! It offers several candidates for an interesting game, including a clash of advance guards, a running fight, a rearguard action at a ford, a field battle and an assault on the enemy camp. Both of the new scenarios are based on the third day of the battle of Lubar on 16 September 1660. The historical version represents an attack by the Poles and Tatars on the enemy camp. The second is a What If scenario, involving a battle in the open ground between the two camps. This scenario presumes the Poles adopted a battle plan supposedly put forward by Field Hetman Lubomirski. Both scenarios can be found here. We played the What If version as a multiplayer scenario in 2014 using Warlord Games’ Pike and Shotte and It gave a balanced game. I later converted the orders of battle for the Tercios rules and we played the historical battle in 2016. Last week I played the historical FKaP scenario with Chris and Paul and will play it again this Friday with two more opponents, Kevin and Rupert. I will post battle reports and photos after the second game. Meanwhile, as English language accounts are hard to come by, I have written an account of the battle below. It is based on a few sources, mainly Łukasz Ossolinski and Mirosław Nagielski. The battle of Lubar 16 September 1660

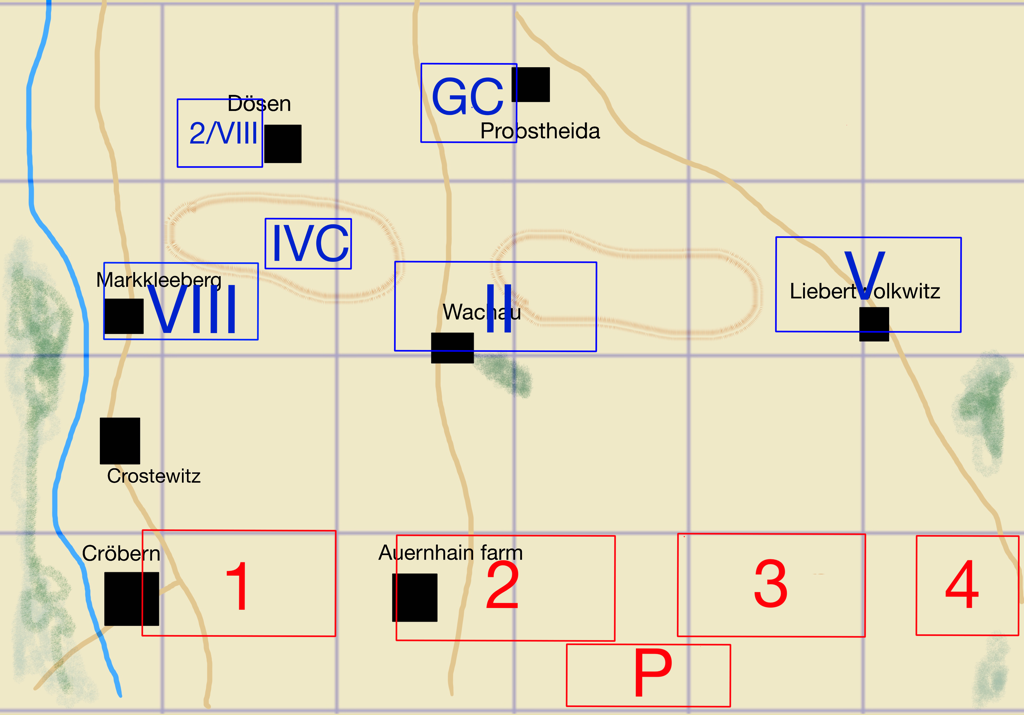

The battle of Lubar was the first act of the Chudnov campaign of 1660, when a Muscovite-Cossack alliance took the field against the armies of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and their Tatar allies in Ukraine. Lubar was in fact a confrontation over several days. It began on 14 September with a chance encounter between the vanguards of the Commonwealth-Tatar army and the main Muscovite-Cossack army led by Sheremetyev and Tsetsura. Having made contact, the two sides made camp within a few kilometres of each other. At this time it was standard practice to fortify in the presence of the enemy, first by placing wagons around the perimeter and if a long stay seemed likely, by digging earthworks. After the initial clashes of the 14th, both sides spent the 15th strengthening their camps and preparing for battle. The Commonwealth and Tatar camps were placed near the town of Lubar, with easy access to fresh water and forage. Sheremetyev and Tsetsura’s camp was well situated for defence with forest to its rear and an emplacement on high ground covering its southern side, facing the enemy. However, it was poorly suited to a long stay, as forage was scarce and its water supply was a marshy stream that was barely able to meet the needs of 30,000 men and their livestock. On 16 September, the opposing forces drew up in battle array, facing each other between their camps. The Commonwealth army had an interest in fighting in the open, where it could take full advantage of its superiority in cavalry. The enemy was believed to be unaware that Field Hetman Lubomirski and his division had arrived in theatre to join Grand Hetman Potocki. According to some accounts, Lubomirski proposed setting a trap, by hiding his troops behind high ground and drawing the enemy further into the open before launching an ambush. For whatever reason, no trap was laid and the whole Commonwealth army advanced on the enemy. In response, Sheremetyev withdrew the bulk of his army back behind his camp earthworks, leaving two forward garrisons: the fortified hill in front of his left, occupied by infantry and artillery with cavalry hidden behind the hill; and trenches in front of his right, occupied by Tsetsura’s Cossacks with light artillery. The action began with an assault by Potocki’s Command on the Muscovite-held hill. The first attack, by Polish dragoons, overran the position and forced the enemy infantry out. The Muscovites counterattacked and retook the hilltop, to be ejected in turn by some of Potocki’s ‘foreign’ foot. Meanwhile a cavalry fight developed around the base of the hill, with both sides feeding in reinforcements. The hilltop may have exchanged hands again in the course of the fight but by late afternoon it was in Polish hands and the Muscovite forces had withdrawn to their main camp. With the hill in his possession, Potocki ordered his troops to prepare to assault the main enemy camp. However, as his infantry formed up in front of the Muscovite earthworks it was disrupted by heavy artillery bombardment and this evidence of Muscovite determination, combined with the advanced hour, prompted Potocki to call off the assault. On the Commonwealth left flank, Lubomirski’s infantry attacked the Cossack forward trenches and eventually cleared them. Again, given the late hour, Lubomirski did not wish his troops to go on to attack the main camp, from which the Cossacks kept up a determined fire. At this point, according to Polish eyewitnesses, an incident occurred that led to the fight restarting. Throughout the day, the Tatar contingent had been coming and going from the field, harassing the enemy with bow fire and looking for weaknesses around the enemy position. Shortly after the Cossack trenches had been cleared, a senior Tatar warrior fell wounded from his horse in front of the enemy camp and a group of Cossacks jumped out from behind their earthworks to take him prisoner. Seeing this, those Tatars in the vicinity rounded on the Cossack group, saved their wounded comrade and amidst the confusion, pursued the enemy back inside the camp. More Tatars followed and were joined by Polish horse and a regiment of foreign foot, all of whom broke into the Cossack earthworks. The infantry commander believed the Cossacks were breaking and urged that the breach be exploited, but Lubomirski insisted that all troops return to Polish lines. The day therefore ended with the Commonwealth army abandoning its gains on both the left and right wings and retiring to its own camp. The fighting on 16 September illustrated the strengths and weaknesses of the opposing armies. Sheremetyev and Tsetsura were outclassed in the cavalry arm so unlikely to win a battle in the open. Potocki and Lubomirski meanwhile had too few infantry to carry the enemy camp by storm. Sheremetyev decided to stay behind his earthworks and wait to be reinforced by Chmielnicki’s 20000-strong Cossack army, which was only a few days’ march away. Potocki and Lubomirski laid siege to Sheremetyev’s camp. Over the days that followed, the Muscovite/Cossack camp, hemmed in by the Commonwealth/Tatar blockade, began to suffer from the poor water supply and limited access to fodder. Moreover, Chmielnicki showed no signs of advancing to reinforce Sheremetyev, despite exhortations to hurry up. On 26 September Sheremetyev retreated to his forward supply depot at Chudnov, pursued a little belatedly by the Commonwealth army. The next day, the two armies settled down again in much the same situation as before, with Sheremetyev blockaded in his camp by the Poles and Tatars. There would follow several minor engagements, a battle at Słobodiście and the desertion of his Cossack allies before Sheremetyev was forced to surrender and marched his army into captivity. As events turned out, the confrontation at Lubar on 16 September had been the high point of Muscovite fortunes.

0 Comments

Late in 2018 I posted some house rules for adapting For King and Parliament to campaigns in Eastern Europe. These included unit statistics for Cossack and Commonwealth armies, around the time of the Berestechko campaign of 1651. Recently I extended the stats to cover Muscovy. I have been rereading an account of the 1660 Cudnów/Chudnov campaign, in which a Muscovite army advancing in Ukraine was checked and later defeated by the joint Polish forces of Lubomirski and Potocki. 1660 offers lots of scope for scenarios, including a meeting engagement, a set piece battle with a surprise twist, a rearguard action and an assault on a fortified camp. I have three different accounts of the campaign including detailed orders of battle and it cries out for some wargames.

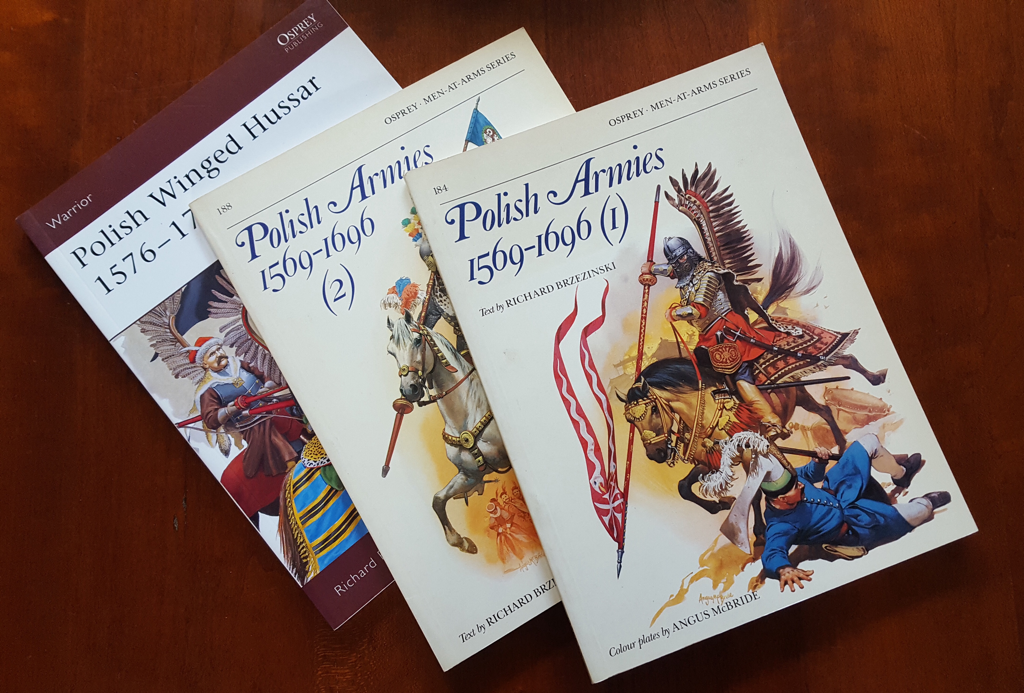

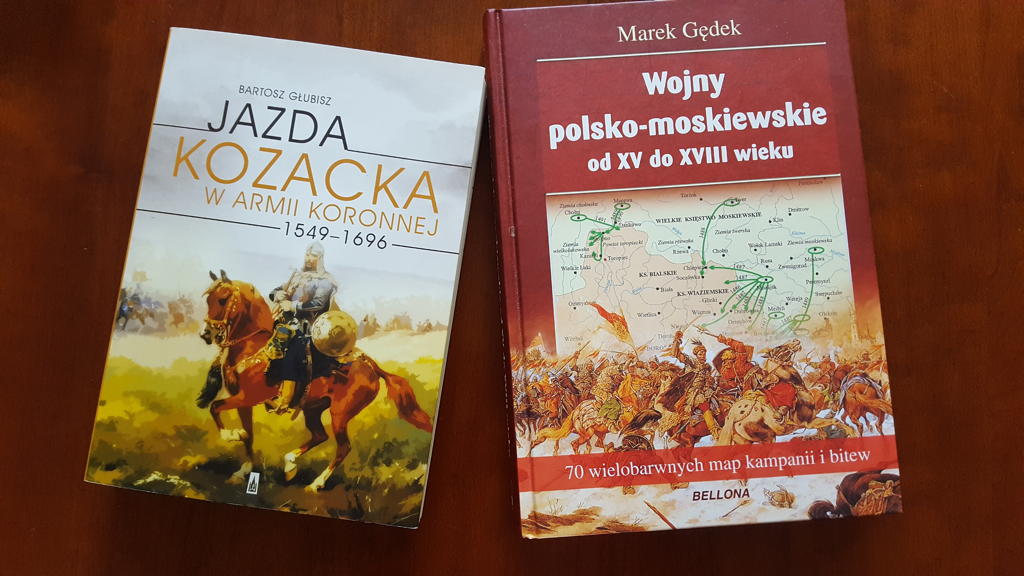

. Back in 2015 and 2016 we fought several games based on 1660, first using Pike and Shotte and later using the Spanish set, Tercios/Kingdoms. Both rules gave satisfying games and I particularly like the mechanisms in Tercios, but I’d love to see how the bigger actions in particular play using FKaP. The first scenario I plan to run is the battle of Lubar, in which the Muscovite general, Sheremetyev, offered battle in the belief that he outnumbered the enemy. It was his first and only foray into an open field. I have uploaded the new unit stats and FKaP army lists for Cudnów here, I am still working on the map and scenario for Lubar and will put this up when it is a bit more polished. In a recent blog comment, Neil Burton asked if I could provide some sources for warfare in 17th Century Eastern Europe. I’m afraid most of my detailed sources are in Polish but there are some useful Ospreys and a growing collection of material in English on the Intranet. Polish Armies 1569-1696, by Richard Brzezinski, is published in two volumes by Osprey (numbers 184 and 188 in the Men-at-Arms series). Volume one concerns the ‘national’ Polish formations and volume two is about the ‘foreign’ section. The illustrations by Angus McBride are particularly good. These books only suffer from the limitations of the format: while a great introduction, they barely scratch the surface of the wars of this period. Richard Brzezinski wrote another useful book for Osprey in the Warrior series, published in 2006, called Polish Winged Hussar 1576-1775. Another really helpful source of information are the rules With Fire and Sword, by the Polish company The Wargamer. They provide lots of information about the different troop types as well as campaign backgrounds and tailored orders of battle. I am not attracted to the rules themselves but they are still worth getting for the background material and illustrations. On the Internet, there is a lot of English language material on Wikipedia. The following links are good starting points and each will take you to several other useful pages, especially about battles. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deluge https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khmelnytsky_Uprising https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Northern_War https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russo-Polish_War_(1654-1667) The following site is dedicated to Polish renaissance warfare. http://www.jasinski.co.uk/wojna/index.htm The last site to recommend is the home page of a re-enactment society, which contains a varied mix of useful articles, from dress and equipment to discussions about tactics. I have spent a lot of time on this site and really enjoy searching it. http://www.kismeta.com/diGrasse/PolishHorseArtillery.htm In case you speak Polish, these are books I have picked up for myself in recent years. New titles appear regularly and it is worth entering the name of a battle on Amazon to see what comes up. I found the two books about Cudnów (1660) that way. i wish this period and theatre was easier to access, since I find it so fascinating. But by looking here and there across the Internet, you will find a great deal of interest.

When we visited Kraków in October, I picked up two accounts of the Berestechko/ White Chapel campaign of 1651, in the fourth year of the Cossack uprising against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. One is about the whole campaign while the other looks in detail at the part played in it by the Lithuanian army under Grand Hetman Janusz Radziwiłł. Apart from a few Wikipedia articles, I knew nothing about this campaign, but was ready to pick up any book I could find about wars in the 17th century. I'm very glad I did. The History Since the uprising began in 1648, the Cossacks led by Khmelnytsky had inflicted a string of humiliating defeats upon Commonwealth armies. On one occasion, a Polish force had fled in panic just at the sight of the Cossacks and their Tatar allies. King Jan Kazimierz was determined to turn the tide in 1651 and two armies were levied for the year's campaign. The larger, Polish army led by the King in person operated in the south, while the smaller Lithuanian army invaded Cossack territory from the north. In several encounters through the campaign, Polish and Lithuanian forces restored their martial reputation. The year saw a series of engagements adaptable for wargames. They included cavalry raids deep into the enemy rear, opposed river crossings, several rearguard actions and two major battles, Berestechko and Biały Cerkiew (White Chapel). After the latter battle the two sides signed a truce that brought the year's campaign, but not the war, to an end. he Game On 27 December Keith and I played a game of Tercios, based on the battle of Loyev (Łojów) on 6 july 1651. At this battle, Radziwiłł forced a crossing across the Dnieper river, a key strategic point on the road to Kiev. The crossing was held by a Cossack force of 1000 men, entrenched along the riverbank. Radziwiłł managed to turn the position by sending a detachment of 2500 horse and dragoons under Mirski, several miles up river, that crossed unopposed, came back along the opposite bank and surprised the Cossack defenders while Radziwiłł forded the Dnieper in their front. Nebaba, the Cossack Hetman in the region, raced to Loyev with his army of 15000 to restore the position but was too late. He inflicted much damage on Mirski but was then assaulted by Radziwiłł. Nebaba died on the field and his army fled. Our game began after Mirski had defeated the original Cossack force and just as Nebaba arrived on the scene. Mirski's objective was to hold Nebaba off long enough for Radziwiłł to ford the Dnieper. Nebaba needed to brush Mirski aside and bring the ford within range of his muskets. He had just five turns to do this. If he had not brought his guns within range of the ford by then, too many of Radziwiłł's troops would be considered to have got across. In our game Keith took the role of Mirski and I was Nebaba. His force consisted of one unit of Hussars, five of Pancerni and three of Dragoons. Nebaba commanded eight units of foot and four of horse. Keith deployed forward, with his Dragoons on a low ridge, flanked by cavalry. I put all my horse on my right, aiming to outflank Mirski and make for the ford, while my foot would maintain pressure from the front. Phase 1: the left wing Lithuanian horse intercepted the Cossack horse and a seesaw Melee followed, in which the Lithuanians gained the advantage but accumulated a lot of casualties. Nevertheless they achieved their aim of stalling the Cossack advance on the ford. The Lithuanian right demonstrated before the Cossack infantry but gave ground. Phase 2: the Lithuanians assaulted the Cossack centre, disordering and then running down two Cossack foot regiments. In Tercios, it is particularly dangerous for formed infantry to fall into disorder near enemy horse. To top it all, a Pancerni unit, having broken through Cossack lines, ran down Nebaba, netting 3vps for Mirski. The Cossack left closed on the Dragoons along the ridge, only for the Dragoons to mount up and withdraw to directly cover the ford. Phase 3: the Cossack left pursued the Dragoons towards the ford but its centre and right continued to struggle with the Lithuanian horse. In the last turn of the game, Lithuanian losses started to rise due to accumulated wear and tear, but they had done enough to keep the Cossacks away from the ford and so won the game. The Tercios rules

This was a great game and Tercios worked very well. The order card system adds tension and excitement, with challenging decisions for players, on both original orders and the sequence of activating units. The mechanics are easy to remember and apply. So far we haven't felt the need to add house rules, which is a good sign! We did however use modified unit stats for the Cossacks. Those supplied in the rules are insufficient to recreate a Cossack army of this period. It's not unusual, but the rules' authors seem not to know that the Cossacks were a predominantly infantry army. The units described in the Kingdoms supplement are fine, but they are missing the formed infantry that made up 90% of the Cossack army. When I next have access to a standard computer, I will post the scenario for this battle. After spending four nights in the wonderful city of Kraków, we came home wondering why we had left it so long since our last visit. The Wawel Castle is a fascinating place, and the Armoury museum is beautifully presented. Its focus is on late medieval and Renaissance arms and armour. In one room, the walls are lined with Hussar armour, mostly 17th century. Stunning. The horse furniture is quite beautiful too. There are some great bookshops in the city too and I brought home two accounts of campaigns against the Cossacks in 1651, a history of Polish-Muscovite wars from the 16th to the 18th centuries and a history of the Polish Cossack cavalry, or Pancerni as they came to be known. So what else is there to do but plan another Polish-Cossack wargame? I have been painting 15mm commander figures and a new unit of Petyhorcy (Lithuanian Spear-armed Pancerni), ready for a game on the 19th. We'll be fighting Slobodyszcze, a scenario I've been cooking for months. There is an excellent map of the field in one of my new books and the table should look pretty fine. I don't like to post scenarios until we've tested them but am hoping it will give a good game. We'll be using Tercios, a rules set that I think deserves to be better known. Unfortunately its online support is a bit limp, although things might improve soon with the release of a line of 28mm figures.

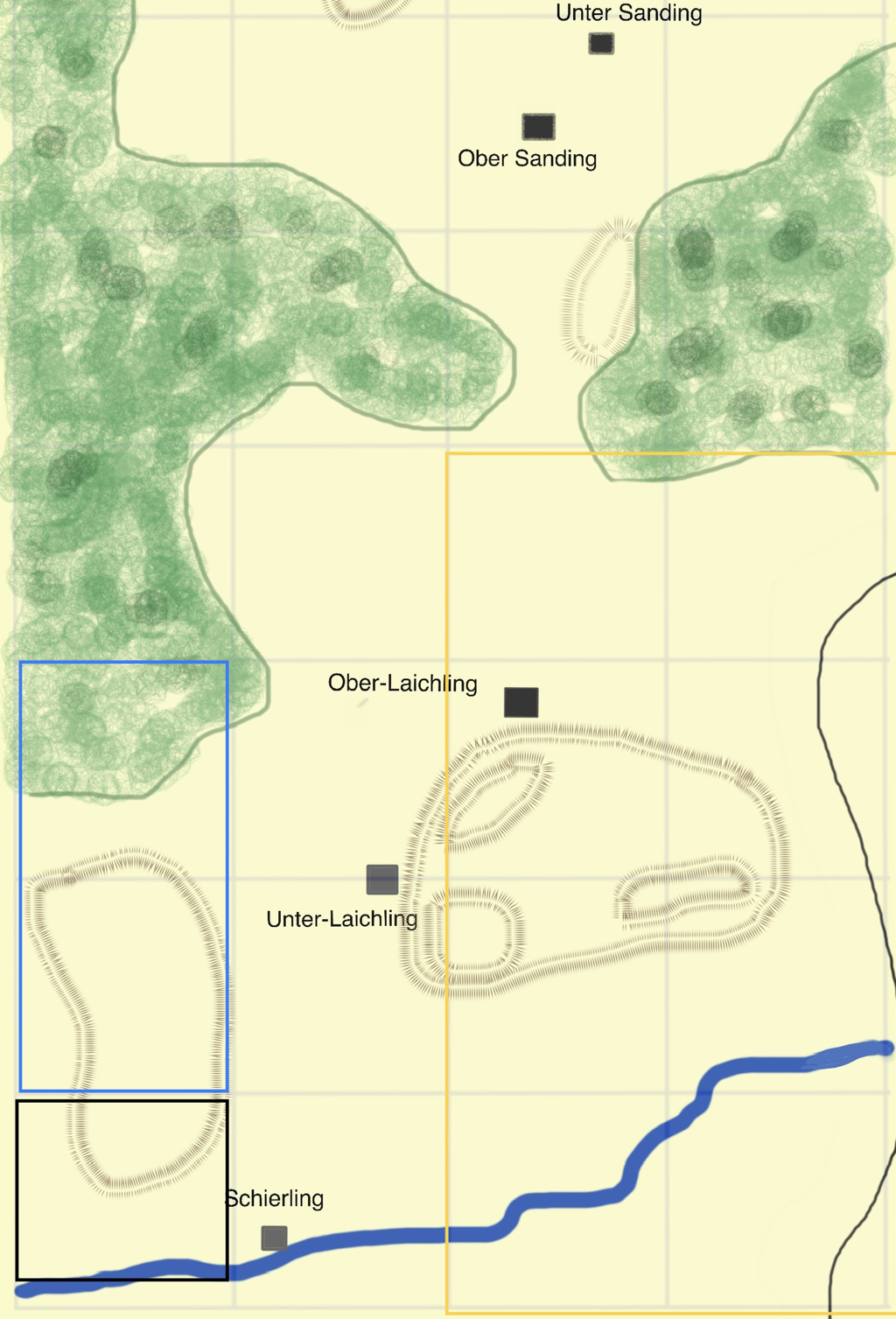

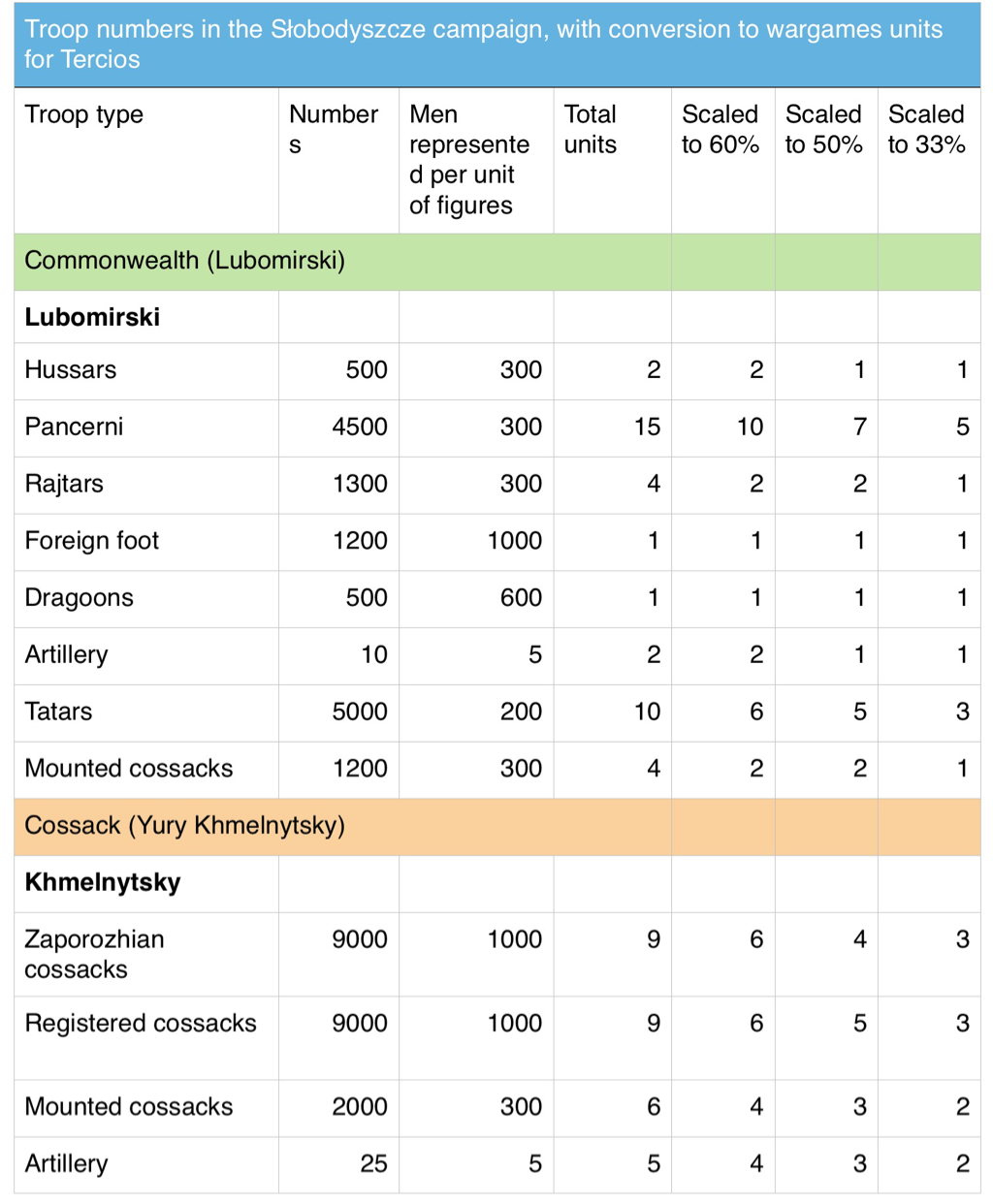

I have produced a Tercios army list for the battle of Słobodyszcze, based on Łukasz Ossolinski's study of the 1660 campaign. It results in two pretty large wargame armies so I created further lists at 66 and 50% of starting strength. These broadly follow the proportions in the real armies, but with some types a little over -represented, especially hussars and Polish foot. For games using Pike and Shotte or Maurice, the number of mounted units should be halved, since cavalry units in Tercios are squadrons not regiments. However, the size of units should be roughly doubled so the broad numbers of figures remains the same. The Commonwealth army is pretty straightforward to represent. The shortage of Foot is striking: Lubomirski deliberately selected a fast moving, mostly cavalry force to surprise Khmelnytsky. The Cossack army is tricky to represent. It included a great many troops who had mutinied against their Commonwealth paymasters and joined the rebellion. In Commonwealth pay these had been known as Registered Cossacks. They wore uniforms and were better trained and experienced than the Zaporozhian regiments recruited direct by Khmelnytsky. In the absence of reliable information about the make-up of the army, I arbitrarily divided the Cossack regiments 50-50 between Registered and Zaporozhian foot. In gaming terms the Registered troops have slightly better staying power although both fight well. Another task is to represent the defended wagons around the Southern perimeter of the Cossack camp, the so-called Tabor. In the battle, Khmelnytsky lined his wagons with part of his force but held back several formed regiments which counter attacked the Commonwealth and ejected them from the camp. I allowed the Cossack player to convert up to half of its regiments into defended wagons, on a one-for-one swap. The next task is to produce the map of the battlefield. I have started one on Sketchpad, using the map on Wikipedia. It's a pretty basic one but should do the job. I just wish I had more talent for producing a polished final product. I have just finished a new unit of Polish 17th century dragoons from the Wargamer's Fire and Sword line. I am quite pleased but the dismounted poses are almost like old flats. I guess they must be older sculpts as they are much less animated than other Wargamer figures I know. Still, it's good to have another régiment in the line. Finishing the dragoons has got me looking at the 1660 campaign again. I am working up a scenario for the battle of Słobodyszcze (Polish spelling), between a Cossack army and a smaller Polish attacker. I plan to play it with the Tercios rules by el Kraken, but as few people seem to have discovered these yet, I will try to make the scenario adaptable to any rules. This battle gives the chance to pit winged hussars and Pancerni against defended wagons and Zaporozhian foot. Despite the spin put on the outcome in the Polish commander's memoirs, it was a tactical repulse for the Poles, albeit leading to a strategic success in the end. As so little is available in English about the battle, I have written a longer background note than usual, relying on a study by Lukasz Ossolinski. I have included it below. I find it fascinating that the battle is the cause of controversy even today, with Russian, Ukrainian and Polish historians all looking at it through the prism of today's murky politics. The Battle of Słobodyszcze

1660 saw one of the most eventful campaigning seasons in the 13 Years war between the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Muscovy. Muscovite armies were active in both Lithuania and Ukraine, taking maximum advantage of the Commonwealth's weakened condition after the years of Swedish devastation of Polish-Lithuanian lands known as the 'Deluge'. In Ukraine,Voivod Sheremetyev led a combined Muscovite-Cossack army against the army of Grand Hetman Stanisław 'Rewera' Potocki. His objective, in cooperation with the Cossack army of Yuriy Khmelnytsky, was to defeat Potocki, take Lvov and perhaps threaten Kraków. Khmelnytsky's army was slow to muster and risked delaying the start of the campaign. Anxious not to lose time, Sheremetyev set his army in motion, having secured Khmelnytsky's promise to join him in the field. First contact with Potocki took place at Lubar on 14 September. Sheremetyev quickly discovered that his enemy outnumbered him by around 40,000 to 31,000. Potocki had been reinforced by the army of Field Hetman Lubomirski, fresh from campaigning on the Baltic. After a sharp engagement in which Potocki had the upper hand, Sheremetyev decided he could not win an open battle without reinforcement. He withdrew into fortified camp, first at Lubar and subsequently at Chudnov, intending to wait for Khmelnytsky to arrive and catch the enemy between their two armies. Potocki meanwhile laid siege to the Muscovite camp, placing his own fortified camp to the South of the Muscovite position. On 5 October, news reached Potocki that Khmelnytsky's 20,000 strong army was approaching from the South East and had reached Słobodyszcze, 27km from Chudnov. Potocki now faced the prospect of being caught between two enemy armies that would outnumber him by 50,000 to 40,000. Potocki and Lubomirski reacted to this threat by splitting their forces. On 6 October Lubomirski set off for Słobodyszcze with a cavalry-heavy force of around 14,000. Meanwhile, Potocki shifted the main camp to a stronger position to the West of its original location and prepared to confront a Muscovite breakout attempt. Lubomirski reached Słobodyszcze around midday on 7 October, to find the Cossacks encamped on a hill on the far side of the river Hnilopat. The Cossacks had not fortified their camp and scrambled to form a defensive position, forming a hasty barrier of wagons facing the Commonwealth advance. Cossack infantry in a fortified position was famously tough to dislodge, especially by a force lacking a strong infantry contingent of its own. Lubomirski therefore decided to attack almost directly from the line of march. After forcing the river Hnilopat, Lubomirski divided his army into three groups. The centre and left attacked the Cossack position from the south, while the right worked its way round to the east of the enemy camp. The centre and left broke into the camp, reaching as far as Khmelnytsky's own tent but losing cohesion in the process. At this point a Cossack counterattack bundled them out again and back down the hill towards the river. Only now did the attack by the right wing go in and was soundly repulsed. Lubomirski mounted another attack from the South but could not match the initial success. He withdrew across the Hnilopat at nightfall. On 8 October Lubomirski was recalled to Chudnov by Potocki, who was facing a breakout attempt by Sheremetyev. Lubomirski left his Tatar contingent to patrol the river and rejoined the main army. Khmelnytsky did not pursue. Within days, Khmelnytsky and Potocki agreed a truce; the Cossack contingent within Sheremetyev's main army began to drift away and the campaign would end with the most decisive Muscovite defeat of the war. Politics and rumours There are various theories to explain Khmelnytsky's actions in the 1660 campaign. He was a young, militarily inexperienced leader who had difficulty controlling his senior colonels. One view is that although his initial intention was to join Sheremetyev, he lost his nerve after Słobodyszcze and asked for peace. Another is that he, or more likely some of his colonels, were disenchanted with the Muscovite alliance and planned to see how the confrontation between Sheremetyev and Potocki played out before committing to one side or the other. A still harsher theory is that negotiations with Potocki were already far advanced and that Lubomirski's attack was intended to convince the last of the pro-Muscovite faction in the Cossack army to give up. Finally, some historians even claim the battle did not take place at all: they suggest it was a fig leaf invented to hide Khmelnytsky's betrayal of his Muscovite allies. This last version is hard to credit, given that correspondence survived from different participants, including foreign officers who took part in the battle. Also, if Khmelnytsky had been looking for a convincing reason why he changed sides, he and Lubomirski would presumably have spread the story that he had been defeated. On the Commonwealth side, Lubomirski's actions too have been much discussed. After his return to Chudnov, the Tatar contingent successfully kept Khmelnytsky on the far side of the Hnilopat. If he knew that Khmelnytsky was already in negotiations with Potocki, did Lubomirski need to mount his attack at all? One explanation offered to explain his aggression is that he was chafing under Potocki's command and wanted a slice of glory for himself. Whatever the whys and wherefores, Słobodyszcze provides an interesting basis for a wargame, and the chance to practice some appallingly different pronunciation! I have had some interesting exchanges recently with Michel, a prolific wargamer and driving force behind Opération Zéro, the site for Francophone wargamers in Belgium. http://operationzero.rforum.biz/forum. He is a great supporter of the Renaissance rules Tercios, which he and colleagues play in 10mm. Michel recently started collecting Poles and Cossacks and we have been discussing how to track down useful background in English or French about the period and theatre. Of course the rules By Fire and Sword provide a lot of really useful background, but there is not much else published about the period in the sort of detail a wargamer wants.

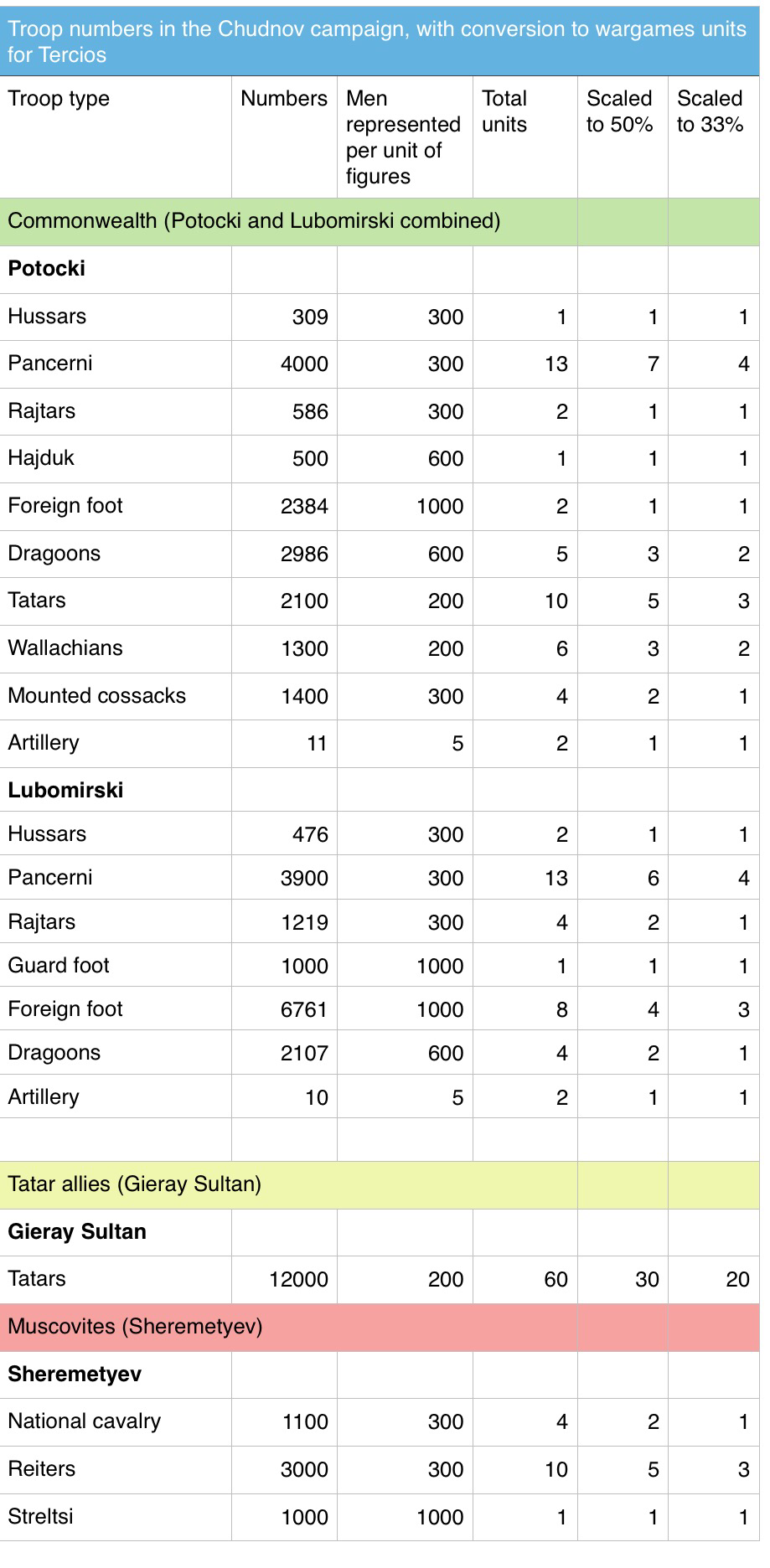

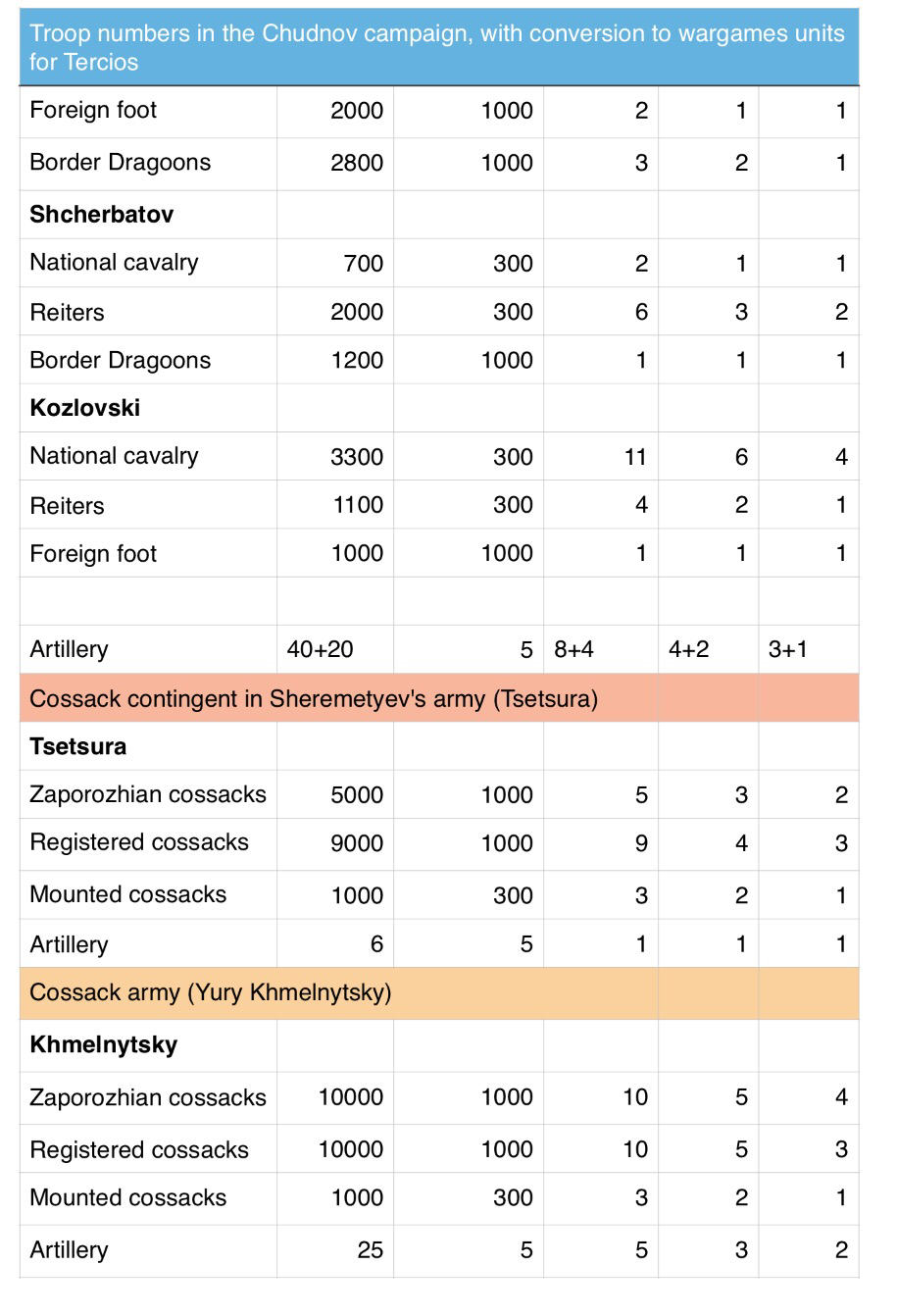

Having been obsessed with the Chudnov (Cudnów) campaign of 1660 for a few years now, I have put together a conversion chart to turn the Orbats for this campaign into units for Tercios. Of course the original data is open to challenge as sources disagree on the numbers involved, but I used the set on which the majority seem to concur. I hope the tables are self explanatory. There is more about the campaign on this website as well as a scenario each for Tercios and for Maurice. I plan to offer scenarios for every engagement of the campaign eventually. These include a meeting engagement, a set piece battle, a fighting retreat and an assault on an entrenched camp. This has been a great weekend. My oldest friend and opponent, Keith, came up for three nights to coincide with Salute 2016. On Friday evening, we played a game with Tercios, repeating the scenario from 1660 in Ukraine that I tried with Ian a fortnight back. As I expected, Keith really took to the Tercios system, especially the obligation to think carefully about the orders for each unit at the start of each turn. In this game I commanded the Polish assault on a Muscovite redoubt. Unlike Ian who succeeded in this role in our previous game, I was repulsed with heavy losses.

On Saturday Keith, Ian, my sons Nick and Will and I spent the day at Salute. I wasn't sure about the Steampunk theme but Keith, who had grown mutton chops especially for the occasion, assured me that there are some good games to be played in dystopian Olde London. I nevertheless resisted the temptation to invest. Instead I picked up some Fire and Sword 15mm Polish 17th century dragoons, a box of 28mm Warlord British WW2 Infantry, 24 Newline Celtic infantry and To the Strongest, yet another Ancients rule set. It was the best Salute I remember of the past few years. Interesting that clubs from Scandinavia are attending these days. One Swedish group laid on a beautiful early medieval display game,using the skirmish rules, Lion Rampant, adapted for larger battles. Inspired by those Swedes, on Sunday Keith and I played two games of Lion/Dragon Rampant. We created two retinues using Warhammer Empire figures but agreed not to use magic or monsters, so in essence our forces matched the Lion Rampant 100 Years War lists. One scenario was about collecting taxes in a border village and the other required one side to escort a convoy from one corner of the table to the other. The sense of storytelling was strong and the rules worked very smoothly. We each won one battle, so the score was two to one in Keith's favour by the end of the weekend. That evening we were joined by friends who don't wargame but do have a fascination for history, so we ended the weekend as we had started it, engrossed in conversation about Wellington in the Peninsular. A pretty hear perfect few days. If only I had taken more photos... Our first run through of the Tercios rules had a varied selection of troop types to see how they coped under the rules. We played turn one collaboratively, placing order counters face up and discussing their expected effects. From turn two we placed orders face down but still agreed to set up some particular situations to see how they played out.

Our conclusions were: It is great fun and quick to learn. Placing orders really makes you think about your force. The reaction function of each order enlivens the game no end and allows opposing units to interact naturally and convincingly. For example, some Polish Hajduks assaulted a unit of Registered Cossacks, who fired at them as they closed, inflicting some damage but not enough to stop the attack. However, the Attack in turn wasn't as decisive as it could have been so the Hajduks disengaged. Cavalry combat can be brutally quick, especially if lances are involved. The rules for commanders seem a bit complicated and there are a great many traits available to choose from. I expect they will feel less complicated with experience and it is welcome that commander models have a real part to play in the game. But I'm pretty sure already that we will outlaw some of the more 'magical' traits, which behave almost like Warhammer spells. Kingdoms The Kingdoms supplement has some interesting rules to suit Eastern armies, such as the ability of Tatar bowmen to fire and evade. The Tabor and Gulay Gorod are well represented and Polish Hussars are suitably powerful but not superhuman. I had reservations about some of the interpretations of Eastern troop types. For example, Polish Pancerni are billed as heavy, presumably because their name means 'armoured' in Polish. But these troops were no more heavily armoured than Hussars and indeed were originally known as Cossacks: they only acquired their new name after the start of the Khmelnytsky rebellion to distinguish them from Cossack insurgents. Another thing that puzzled me was the absence of Cossack infantry besides the Plastun skirmishing companies. These companies can be converted to Tabor but this isn't enough: I expected to see stats for Registered and Zaporozhian Cossack Infantry as well. The Cossacks were mainly infantry armies at this period, having the reputation of producing the finest infantry in the region. Registered Cossacks constituted some of the Polish army's best Foot regiments, when they weren't in rebellion! And they did not always fight from wagons. I was therefore a bit disappointed but not for long. With these rules it is easy to adapt the stats to suit your own prejudices. So I made up my own stats for formed Cossack infantry, drawing on Musketeer and Hajduk stats, and simply dropped the Pancernis' heavy status. The verdict after first play? Very positive. PS I have gone into a bit of detail because superficial rules reviews are a pet hate. But if I have banged on for too long please excuse me - and let me know, so I don't repeat the mistake in future. |

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed